Maria Zef (Vittorio Cottafavi, 1981)

Fred Junck: We’ve just watched Maria Zef and we’re aware it’s a very old project of yours; in fact, I understand it should have been your first film?

Yes, that’s right. I wanted to do it in 1938, after having just left the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, which I had entered in 1935. I thought I’d immediately find producers ready to say: ‘So you just finished the Centro Sperimentale? You’re a director! Come, come! What film do you want to do?’ And that’s the film I wanted to do. You must know that, back then, in the Ministry for Popular Culture, which during fascism was responsible for cinema, there was a bureau assigned solely to filter out what should be shot, that is, to approve the theme and the screenplay in advance. I brought Paola Drigo’s novel under my arm and said ‘This is what I wanna do!’ Then one of the employees — a fine man of letters, a playwright — told me: ‘Listen, pal. Between you and me, there’s a rape…’ And I: ‘Don’t worry, the rape doesn’t interest me; what matters is how a young girl can have such a relationship with her uncle that it leads to rape. It’s the interior movements of the characters that interest me, psychology, sentiment. Not the rape in and of itself. So don’t worry about the rape, it won’t be shown.’ And, indeed, even today, forty years later, we don’t see the rape.

Then he said: ‘But there’s a murder.’ And so I tried to explain to him that the girl does not kill for revenge because he is raping her, but because the little sister would remain alone with him, who is the father: in fact, she has discovered the young girl is indeed her mother’s daughter, but the uncle is the real father, because her father was already dead when her sister was born. Therefore, it would have been incest.

So, when the uncle sends her to go work in the city, the girl is desperate, she tries over and over again to make the uncle leave the sister to her, the sister to whom she has practically become a mother. She has taken over the role of mother in regard to the little girl. At that point, there’s no other choice but to murder the uncle. She kills him whispering: ‘The little girl, my sister, no, not my little sister!’ And that’s what interested me: to reach this ‘Not Rosute!’, not the murder of the uncle. The murder of the uncle, it’s enough for me that it’s clear. Moreover, she’ll kill him with an instrument typical in his job, he who from the beginning to the end of the film always works alone.

Maybe the censorship could have let it pass, but at that point I made a fatal mistake, because when he said to me, ‘But these people are poor, they’re hungry and they work so much, it’s misery’, I answered, ‘Well, there’s nothing I can do about it this time. There’s misery, the underdevelopment of poor people who work in the mountains, among a thousand other hardships. I can’t get rid of that at all.’ So he concludes: ‘Listen, take back your proposal and forget about it, because you’ll never get the permit to make a film on the misery of the Italian worker.’ That was fascism: a dressing-up, a masking of, a retreat when faced with the problems of life. The only thing that mattered was not touching the ideals of fascist life and work. It was... well, nowadays everybody knows what fascism was.

After the war I once again tried to get the film made, but that didn’t work several times because producers said to me: ‘How do you expect the audience to be interested in seeing the story of miserable hungry people? Not a single spectator will go see it.’ I’d answer: ‘Listen, there are real feelings, there is suffering, it is also somewhat pathetic, there’s a comical component to it. Imagine a nine-year-old kid, a fourteen-year-old girl and a dog. These three together are already comical in themselves. There’s also a sentimental side to it: a little kid, an eight-, nine-year-old girl — that captures the hearts of the audience. That will bring in spectators!’ No, nothing I could do. In the meantime I abandoned cinema and started doing television. At a certain point, almost two years ago, when Rai3 started thinking about regional programs, I thought, ‘That’s a good occasion, I should make the most of it.’ And I suggested this film which is absolutely regional, spoken in a language which is not Italian but the local language, Friulian or, more precisely, ‘Furlan’, which in practice gives the whole film a particular aspect, which was precisely what Rai3 was looking for.

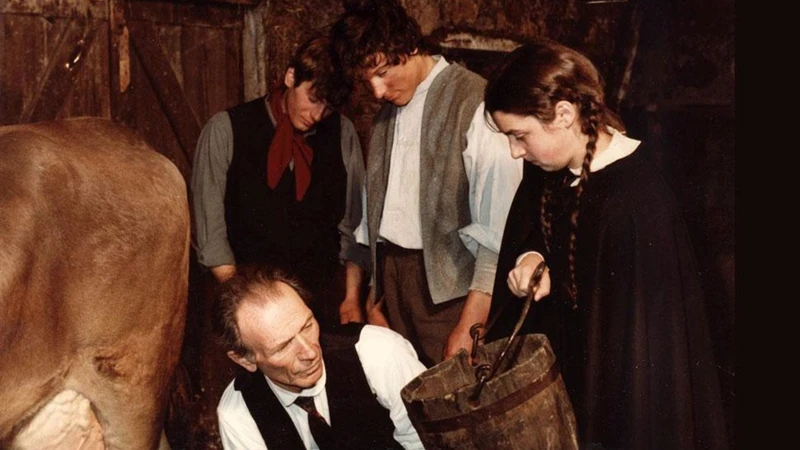

They asked me: ‘How much does it cost?’ ‘Oh, very little’, I answered. ‘I won’t use any actors, just locals; I’ll shoot it live, no sets, no studios; I’ll do everything from reality, both interiors and exteriors.’ So they estimated a budget, an extremely reduced budget, and said to me: ‘Fine, that’s O.K.’ I didn’t need a big budget, you’ve seen the film, there’s only what’s strictly necessary, nothing else. It would have been foolish to ask for more than what was necessary.

And so, finally, forty years later — from 1938 to 1982... that’s forty-four years later — the film got made! If you’ll forgive the joke, I’d say my first work runs the risk of being my last! Whether that’s a joke or not, time will tell.

Jean A. Gili: Regarding the budget, how many million lire did the film cost, precisely?

It’s hard to say with precision because I used people who were on Rai’s internal payroll, meaning that the operators and technicians were the same ones from TV. They didn’t enter the budget. So I’d say the budget — not the estimate made by the network, calculated based on the actual amount they invested, but the real cost of the film — is somewhere around 320–380 million lire. More or less.

It’s shot in 16mm. For me that wasn’t a problem because by now 16mm has a level of quality, of image definition which is rather good; moreover, 16mm cameras are really light and handy when you’re shooting in the snow, up in the mountains. In that case, it was better to avoid material that was too heavy, and use things which we can easily move around without causing too many problems. So 16mm works fine. The print you just saw was blown-up to 35mm.

FJ: Rai sold the film to a festival: that was when they blew it up to 35mm?

The film was blown-up to be sent to Canada, where circa 150.000 ‘Furlans’ live and work. The Canadian audience in Montréal is French and also Italian. So we asked: ‘Do you want a print with Italian or French subtitles?’ And they told us: ‘Make it in French.’

The film went to the Montréal festival, outside of competition, then it passed by all French cities in Canada. It was seen everywhere Italians can be found, in particular Friulians. It seems good to me that Rai does some sort of cultural promotion, so to speak. It’s the first time a film is shot in this language, in Friulian. I hope it won’t be the last…

JG: In the film’s presentation, you said you don’t remember much about the first draft of the screenplay. The final script, the one you used for the shoot, how faithful is it to Paola Drigo’s novel?

In its structure, it’s very close. It distances itself a bit in situations with the characters. I always thought the theme was that of an acquired motherhood. Mariute, that is, the fourteen-year-old girl, realizes she has become a mother the day her mother dies, which happens at the beginning of the film. From then on, the eight-, nine-year-old girl sees Mariute as her mother. And she attaches herself to her with the desperate strength of a girl who’s lived through the shock of finding herself without a mother, who tragically died of an illness in the plains while trying to make some money to survive. I wanted to make it as explicit as possible that their budding relationship isn’t one between sister and sister, but one between daughter and mother.

On the other hand, what interested me was the internal point of view, the image that shows the character’s interiority. It’s an old fixation of mine, you’ve seen several films where I tried to get to a situation where I could penetrate the character. Even in a love story like Una donna ha ucciso there’s this attempt to penetrate the interiority of the character, of the characters.

They’re peasants, mountain folks, people who don’t talk much, modest, who tend not to talk about their most intimate feelings. So they don’t express themselves, and it’s up to us to enter them so we may understand what it is they do not express.

I’d done the same thing in Il taglio del bosco, twenty years ago. It’s a very similar story, I mean in its style, a story that takes place among lumberjacks. In that case too, we’re talking about extremely humble, modest people, who aren’t capable of expressing themselves, of communicating with others except through a simple feeling of friendship, of solidarity among sufferers. And I shot it in a corner in some woods, I managed to do it like that, and it’s one of those dreams life allowed me to realize. For that I’m thankful to life, to Rai, to chance, which allowed me to find the ideal performers for the film.

Because to find locals, who’ve never acted before, who aren’t actors, and who can be so believable, to the point of becoming themselves characters, is a rare stroke of luck which must be stressed. If you take in consideration that we’re talking about at least seven main characters, and that they’re all perfectly outlined in their physiology, psychology and morality, well, I wonder who helped me find them! Who helped me, I mean, what strange impulse helped me find Mariute on the very first day? To immediately find the little Rosute, the very first time we went after a girl, among eleven candidates — just eleven, that’s how despondent I was... And to have the courage, but also the ultra-precise intuition, to choose a poet, a playwright, a former executive of Rai named Siro Angeli to play a peasant. Because his origins are those of a peasant, he comes from Cesclans, a little town in the mountains.

FJ: So Siro Angeli is from Friuli? He’s not dubbed?

Yes, he’s Friulian. He speaks the language, he’s not dubbed. No character is dubbed. The whole film is live, you can’t dub a man who’s not an actor, who’s not a professional!

FJ: I ask you that because so many Italian films are dubbed. It’s interesting to know yours isn’t.

There isn’t a single dubbed word. It’s all live, with its qualities and defects. You can feel it even in the sound effects, which are real noises...

FJ: Yes, indeed, the sound is excellent. Back to Siro Angeli...

Siro Angeli is a writer who’s worked with me on various screenplays since 1949. In this case he not only wrote, but wrote it in his own language. He’s written poetry in Friulian, but now he is making a film in Friulian. We had some problems with ‘Furlan’, because, you know, in the mountains these old languages somewhat vary from valley to valley. I had to work with characters in the plains, low in the mountains and high in the mountains, and there were linguistic differences which could render the whole incomprehensible. We had to resort to a language, let’s call it the ‘average Furlan’, which could be accepted by all Friulians, leveling out accents and punctuation. It’s what happens in the whole world and it happens there too, there’s the sea, the plains and the mountains, that is, three completely different situations for a same language that has been through changes throughout the centuries. It’s a problem Angeli understands very well, he’s worked on it for years... But the funny thing is that while we were searching for the characters, the actors, I was also very happy to have found the dog. It wasn’t easy to find a dog. I didn’t want a trained, domesticated dog that seemed fake and acted poorly because it was forced to follow orders without understanding what he did. I wanted a dog who knew what he was doing while he did it. A wild dog, in short. We found him amidst four hundred dogs crammed in an abandoned lot near Udine. There, amidst four hundred dogs, I had the luck of choosing the right one. You’ve seen him, he’s a good actor, a good dog.

At that point Siro Angeli told me: ‘Look, you need to find Barbe Zef.’ ‘Don’t worry.’ ‘Actually, I am worried. You’ve found them all, but you still don’t have the slightest idea of who’ll play Barbe Zef.’ ‘Alright, listen, you’ll play Barbe Zef!’ ‘Me?!’ He was very agitated, but I forced him into it, I made him do it. You see, the others didn’t know anything about the world of show business, so they feared nothing, they were ignorant. To execute, to speak: for them it was all natural; after all, they were in their environment. Siro Angeli is an extremely cultivated man, a poet, a playwright, he’d done theater and he knew very well what it was about, and so he was nervous. But he had seen since the beginning how the others acted. I made him start on the third week. First I worked with the others, that way he could see it, understand it, adapt himself. And when he started shooting he was still a little stiff, but he was also starting to relax.

And I had no problems with him, other than that he was incapable of pretending to be drunk! So I said to him: ‘I will give you grappa some day! No, no, you’re right, we won’t do it like that! But you’ll drink the grappa anyway, because when you drink from the bottle you don’t make the right face, that grimace we do when we ingest alcohol. So, I’ll let you spit it all out in between takes, but when we’re filming you must drink it!’ So he drank the alcohol, made the correct face and then he spat it all out.

Actually Angeli is an extremely gentle, educated, nice man. He played a role that up until the last moment is rather tough, rather unpleasant. Only in the last scene, before he dies, does he become more human. And he didn’t come up with excuses, he didn’t say, ‘Listen, I don’t want to play a negative character.’ No, he accepted that he was a negative character, who, in the end, in the moment of death — I won’t say he feels regret — shows a glimpse of his human side: he isn’t a dirty dog, he’s just poor.

JG: There I think we can see not only the qualities of the performer but also those of the mise en scène, because that whole final sequence is shot from above, and we can only see the back of his neck. He’s already in a repentant position, waiting for the blow of the axe, as if he was going towards death.

You’ve understood it perfectly. Yes, since the beginning I didn’t want any faces to be seen in the last scene, but rather that the voices were heard, that the napes were seen. Also for a distancing effect, as if we were moving away, almost horrified by what’s about to happen. The result seems good to me, in the sense that we managed to obtain what we wanted; and, given we didn’t have professional actors, there were no problems, because, you know, professional actors they say: ‘What, shoot me from the back? But the spectator wants to see this!’ That’s the typical phrase of the professionals... So, as there were no professionals, I shot it like I wanted to, no problems!

For Siro Angeli it was a personal achievement, because, even if we can say that, sure, little Mariute acted incredibly, Rosute was moving, and that everybody played their roles perfectly, Siro Angeli as the uncle has something more. He found the character’s truth within himself. And that’s owed to his experience as a playwright. He put all of the character’s repressed nature in it. And indeed he expressed it.

Moreover, as you have noticed, he really has the face of a mountain-dweller; he comes from a little town in the mountains and in practice he somewhat went over his own life again, the conditions of his father, of his ancestors, mountain-dwellers like him. He has civilized himself, yes, but fortunately his face has remained that of a man from Carnia.

JG: He’s been one of your most regular collaborators, from a certain period onwards: starting with 1949’s La fiamma che non si spegne, his name has shown up several times again...

I believe he worked for Il boia di Lilla, for which Giorgio Capitani also collaborated, and for other films such as Traviata 53 or Avanzi di galera.

FJ: Let’s go back to the beginnings of your career. I have in my hands a French dictionary of contemporary directors. The entry on you underlines your commitment to popular genres, like the melodrama or the swashbuckler. What do you think about this? Is it true, or did you do these films because you were forced to?

It’s extremely difficult to say exactly to what extent I have been forced or accepted it voluntarily. If you allow me I’d put it like this: whether forced or of my own choosing, from the moment I accepted doing a film I’d get to work with the same enthusiasm, the same will and the same attention as if it were the masterpiece I always dreamed of making. I never cheated. And it’s precisely because of this that even the bad films I made were deemed noteworthy, because I shot them without cheating.

FJ: To me you seem to be in the same situation as that of another great filmmaker, Douglas Sirk, who worked in the exact same conditions, also within genre cinema. Do you know the films of Douglas Sirk?

Yes, I like them. He had a particular taste for a certain type of modern American comedy, a description of the America of today, and he also had a certain sense of humor. To me, I love a sense of humor. Even in the greatest tragedies, even in the Greek tragedies, I’ve always put in a little humor.

Perhaps I’ve said this already in my interview with Présence du cinéma, but I’ll take this occasion to recall that in Antigone — a Greek tragedy which I had the pleasure of filming twice, fifteen years apart — there is a character taken directly from the satyr play: that is, a comical character, which to me represents, for the first time, a Brechtian conception of things. It’s worth noting that, in the apex of Greek tragedy, there is for the first time something which gives the idea of the new epic, upon which Brecht will theorize centuries later. Among the soldiers, when they announce that Antigone tried to bury her brother, there’s this crackpot who fears power, makes some witty jokes and imitates the sounds of nature. He describes the movement of the grass, and the blow of the wind: ‘Vvvvvv!’. In between his words, he says ‘Vvvvvv!’. In sum, a real comedic character, from the satyr play, standing there in the cruelest moment of the tragedy, that is, in the moment when Antigone’s crime is represented. Then, as I realized that Shakespeare always mixes tragedy and comedy, I told myself that was an excellent idea, perfectly just, that it should be done just like that. I told myself that if Shakespeare had done it like that, then we could go on doing it even today.

And that was very difficult, because neither critics nor audiences are likely to accept that a tragedy be half comical, half tragic, or that a comedy may contain tragic elements. It’s one of the negative aspects of I cento cavalieri, a film which I consider — rightly or stupidly so — to be my best: tone changes constantly, which did not please either the critics or audiences. That’s when I decided to change direction, because I said to myself: ‘I do not wish to go on doing cinema if with this film, which I made according to my own ideas, I wasn’t able to touch audiences.’ Critics, that’s a whole other story. But, faced with such rejection from audiences, I said: ‘Listen, I’ll make television, where there’s an audience waiting for me, millions of spectators every night.’ And I abandoned cinema once and for all. Except if I come back to it some day, who knows, never say never...

JG: I’d like to come back for a moment to the subject of humor. Isn’t that what surprised audiences, perhaps...? For example, the commedia all’italiana is based on a comic and dramatic mix. But in the best films you’ve done, and particularly in I cento cavalieri, there’s a very allusive, subtle humor, not an explicit humor. Isn’t this perhaps what left audiences disoriented?

Yes, maybe. But let me note something for you: the character of Don Gonzalo, played by Arnoldo Foà, is a comic character from the beginning up to the very end. That some situations then become comic-metaphysical, I agree with that. But, audiences could laugh at that first-level humor, even if they weren’t capable of laughing at the second level. When the Duke of Castile talks about the armor — the armor covering the warrior is the first scientific weapon — and, one comparison after the other, one thought after the other, ends up imagining the atom bomb, fine, that’s metaphysics. I don’t expect audiences to laugh at that. But I wanted them to apprehend the fact that the armor was the atom bomb of its time, like the cannon was the atom bomb of the age of gunpowder. You get what I mean, don’t you? It’s dark humor, for sure, but dark in its subtle content, not in its form.

Having said that, I think what ruined my respectable relations with audiences is the fact that I cento cavalieri is a film without a hero. Both goodies and baddies have their flaws and virtues, no one is more hateful than any other. Even the character which we grow the fondest of, after a certain point we realize he’s kind of a jerk, that it’s not worth it caring for him.

Besides that, the story is based on historical events. Once I said it was a phenomenological film, in the sense that we follow events as they happen; no anticipation is built, there’s no dramatic construction. It’s pieces, fragments of history which are linked one to the other only because they take place in the same time and place. The film’s contradictions are the contradictions of history. I thought I’d done something that approached historical truth. And, instead, it seems critics and audiences didn’t like it.

JG: Don’t you think the film was a little ahead of its time?

Twenty years have passed, and until now it hasn’t been re-released. I don’t know if audiences today would accept it more or less. Of course, there are critics who didn’t even go see it, they sent their kids, a friend or a relative to go watch it and then asked them to tell them what happened. ‘Oh well, they whack each other, there are the moors, the Spaniards, all of that.’ They convinced themselves it was a swashbuckler and wrote two lines in the newspaper just to say, there you go, there’s this film.

But there was this one critic who took it very seriously, when it was shown on television, on Rai1, in a brief series of six films. This critic presented it as such: ‘Tonight, we’ll see a film that’s a minor masterpiece of its genre…’ I won’t argue the ‘minor’ part, but ‘masterpiece’ seems a little too much. However, that means opinion has changed drastically since the film was released in theaters...

JG: How was the film received on television?

Favorably. From audiences, favorably. But you can’t get a precise idea of the results, contrarily to a film’s box office. In television you get an indicator, with no box-office. So it’s hard to tell precisely. People may have seen or endured it on their TVs, but we can’t tell if they’d have seen and accepted it in a theater, where one must pay 5000 lire to take a seat.

FJ: Your name is linked to two films where the degree of your participation is unclear. I’m talking about I piombi di Venezia and Le vergini di Roma.

For I piombi di Venezia, things are very simple. The director, Giampaolo Callegari, a dear friend of mine, wasn’t well-received by distributors. So, Giorgio Venturini, the producer, to whom I was preparing Traviata 53, said to me: ‘You gotta supervise this film, otherwise the distributors won’t give me the money.’ And I said, ‘Fine, I’ll do it. Even more so given Callegari is a friend. If I can help him out, it’ll be more than a pleasure.’ But in reality Giampaolo Callegari was a screenwriter, a dramatist, he wrote scripts, and he didn’t have much experience as a director. So, to allow him to work best, I helped him in being quick, in shooting in a spectacular fashion. He was afraid to move the camera because she was unknown to him, he wasn’t used to seeing things through the lens instead of the eye. He didn’t visualize things, he had the mentality of a man of theater.

So I helped him, and sometimes he’d film something while I filmed another, to speed things up. But it’s Giampaolo’s film, it’s his script, his stuff. I helped him in some sequences, in others I gave him some advice, sometimes I shot it myself. In short, it is quite hard to tell what I did and what Giampaolo Callegari did. It’s a four-handed sonata.

JG: That’s important, because apparently it is also your film, to a great extent. And what about Le vergini di Roma?

Le vergini di Roma is an even simpler case. We worked on the script with Léo Joannon, a really good screenwriter who was also a director; he’d made Le défroqué in 1954. Joannon was an extremely refined man, of great qualities, but the Romans weren’t really his thing. Having said that, I hadn’t chosen the actors. Then there was Louis Jourdan, who is a great professional, but who was out of place there, and also it seemed he had a very particular contract. He could make decisions regarding the screenplay, the shoot and the edit. I had no evidence any of this was part of his contract, but from day one I suspected something was wrong.

So, given all the problems the making of this film entailed, this ambiguity in regard to Jourdan’s role and his decision-making powers which were imposed upon me, I decided not to go on with the film. I made it clear in my contract that there was supposed to be no second unit. And when in the second week of shooting they set up a second unit to speed things up, I said, ‘Gentlemen, Saturday I’m leaving; I’ll give you this time to pick another director to finish the picture.’ And so I abandoned the set after two weeks of shooting, which they did make use of, even if I said I did not intend on putting my name on the film.

Carlo Ludovico Bragaglia replaced me as director and he put his name on it. He’s a very well known director in Italy and abroad. He’s made genre films, swashbucklers, pepla, anyway, he’s an excellent professional...

JG: What is left, how many minutes, more or less, of what you shot?

Not that much. A little bit here and there... Because it wasn’t shot in order. Let’s say, some ten minutes, no more than fifteen. If someday you happen to come across a print of Le vergini di Roma, show it to me and I’ll be able to tell you exactly the things I recognize, the things that I shot. Like that, just for fun...

JG: Within the popular genres, during the fifties you mostly did historical reconstruction films, pepla, swashbucklers. And then there were the contemporary melodramas. Which films do you feel the closest to, your costume pictures or the melodramas of today?

They are very different things. The contemporary melodramas are part of the street, of the road I intended to go through in order to penetrate the characters’ interiority, to photograph the soul, instead of just looking at faces... Because to me the lens is something that goes inside people. You look at the picture of a man and you say to yourself: ‘This man is very sick.’ Like that, without even knowing it, and then you find out that a few months later he died of some illness. In other words, the lens revealed the sickness that was inside the man. I think the lens has something sacred in it, something that goes beyond that which we are. But, to exploit this aspect of it, you must help it, you must take on the point of view of the lens, to penetrate inside the characters. And you enter them through their microphysiognomy, their eyes, their attitude, through the movements of the camera and of the actor. It’s like the course of a river that goes from one place to another, and it flows in one direction. This is how I tried to approach the melodrama, to achieve this penetration.

On the other hand, the historical film, the peplum, for me it’s like a big, joyous flower arrangement: colors, movements, scents... It’s a rather simple vision of History, a little childish. We could say, a ‘de-contemporary’ view of history. You may have noticed that in the films set in ancient Rome nobody salutes with their arms raised as in the official gesture, instead it’s a rather magniloquent gesture in comparison to the real Roman salute. In reality, as a contemporary man, I understand very well the greatness of the Romans, who exported a certain type of civilization: wherever they went, they took over other civilizations, devouring them.

You must have in mind, and I think I said this in that interview with Présence du cinéma, that the Roman gods were all foreign. In Roman religion, there are Oriental gods, Western gods, African gods, the savage northern gods of the barbarians... But there is no Roman god. There are Italian gods, but they belonged to other people, not the Romans: the Etruscans, etc. Perhaps the only actual Roman god is Janus, the two-faced god. And this reveals the essence of the Romans, of Roman tradition, of Roman civilization, which is always two-faced. There is good and there is evil, greatness and nothingness, genius and stupidity... That’s a proper Roman god.

What I tried to do, the point of view I tried to adopt — and it’s up to you to tell me if I succeeded or if it did not go beyond my intentions — was to look at the history of the ancient Romans as if it were contemporary to us. And given that we can’t bring the Ancient Romans closer to us, it must be us who get closer to them. Now, to be contemporary to a Roman, to have a feeling of Romanity, what that means is... The Romans don’t make big gestures, but when they move, even when they give orders, the way they make anything, it’s all firmly anchored in a potency, in a caliber that isn’t the normal caliber of other types we see in historical films. I’m not sure if I’m answering your question or if I’ve swayed off-topic.

JG: At the end of the day, all the films you made before moving to television were historical films, in their own ways.

Yes, that was the time. There’s the myth. First historical, then mythical. I’ve made both...

JG: For you, is there a difference between historical films and mythical films?

Yes, absolutely. Facing historical facts, one is man among men. Facing myth, one is man struggling with his own metaphysical creation. That’s myth. And so man, in all ages and even today, has created myths usually divided between the personal myths of each of us and the collective myths. Some economic myths are also collective myths.

At the origins of civilization, myths were much more personalized. The myth contemplated the character, and the character became the myth. For me, Hercules is a myth that has existed and will exist forever because it mixes man, earth and everyday life with the divine, immanence with transcendence. And in Ancient Greece, it was also something to laugh at. For the nth time, I point out that the labors of Hercules are filled with disgusting filth! He had to clean stables, that is... shit, shit and shit! A mythological hero, a demigod who had to empty out barrels of shit. And that gives us an idea of how civilized the Ancient Greeks were, how they mocked their own myths: a man who killed a lion as a kid who now has to move metric tons of shit.

I always liked Hercules: a strong, peaceful character, who loves tranquility, but who’s always ready to fight when he has to. But no more than what’s necessary for him to reach his ends. As soon as he gets what he wants, he gets lazy. I must confess, I too am a lazy man. If I’ve worked much in my life, it’s because I’m super fast: the sooner I finish working, the sooner I can go back to being lazy! I’m an astonishingly active lazy man so that I can calmly abandon myself to laziness!

Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide (Vittorio Cottafavi, 1961)

FJ: You’ve already talked about it, but I’d like to go back to the moment when you left cinema for television. At the time, you were known all around the world thanks to Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide, a successful film in every way. You had great resources available, and it’s the best genre film you ever made.

Yes, it was a success, even financially. A remarkable budget, and also shot in Technirama, which delivers an exceptional image. 70mm...

FJ: Why is it that precisely then you abandoned cinema for television? Afterwards, you only made I cento cavalieri. Were you fed up?

You know very well my reasons. I can make both cinema and television, alternating according to professional reasons. But I realized that with television I entered people’s houses, that suddenly my message reached a million people. While with cinema it only reached two, three thousand people each time the film was projected.

In Italy a hit, a really big hit, is seen by four, five million spectators. Meanwhile, when I adapted Dostoevsky’s Humiliated and insulted for TV, I could rely on 12, 14 million spectators with whom to communicate. An unconceivable number for cinema.

And then... Well, I’m a bit of a moralist. I like to give lessons to my contemporaries, it’s my professorial side, a side that gives me a certain importance. And moralism — which naturally does not equal morality — can be used in TV dramas, in TV programs, in some stuff made for TV, but not in cinema. That’s the second reason.

But the decisive reason for my transition, as I already said, was I cento cavalieri, into which I had poured most of my ideas, most of my aspirations; I thought I’d made a film of a certain interest. Anyhow, it was a film that represented a sort of end goal of my career, one of its possible destinations, the spectacular destination — differently than the metaphysical or psychic one, psychological, interiorized, which represented my other side. But the film was chopped by distributors, it was ignored by critics, rejected by audiences, and at that point I said to myself: ‘Listen, this is a sign…’ I was being offered films each more stupid than the other.

FJ: Westerns?

No, not yet. I had suggested a western. But unfortunately I offered it to Paramount, who had given me a peplum script titled, if I’m not mistaken, Oro per i Cesari [Gold for Caesars], or Golia contro il gigante [Goliath against the giant]... I don’t remember which one it was, but it was nonsense... so, so stupid...

FJ: Oro per i Cesari was then made in 1963. I don’t remember much about it. It’s not a western. So you wanted to make westerns?

At that time they had offered me one of these two, I can’t remember which one... I think United Artists had distributed Ercole or something like that in America. So I made a counterproposal, a story called Un metro de sombra, which in Spanish means A meter of shade. It’s the shadow the protagonist casts over a tomb, a gravestone. When Tom, his general, is buried, he pushes the stone, tilting it. At the Equator, shade does not exist. Wherever he goes, he presents himself as ‘Meter of shade’. It was the story of a pronunciamiento, a fratricidal battle for oil in a Central American state. The two big bosses were in New York, in separate skyscrapers, one facing the other, and those in the Central American country killed themselves for one or for the other, to decide which one of them would get the oil.

When I offered it to them, I was really interested in it. It wasn’t really a western, not in the strict sense. It was, how can I say... adventures, gunmen, pronunciamientos, battles. I was told: ‘But you’re crazy, you just offered an anti-oil film to a company based on oil money!’ So I realized the years had passed, that I was no longer capable of getting by very well and so I moved to television. The only western I wish I’d done was precisely this somewhat moralistic western about the power of money, which leads to so many people killing each other for a few billions of oil dollars, a result which in itself is meagre and pitiful.

JG: In television, did you feel it was very different, the way of working, of filming?

The real differences aren’t aesthetic. It’s about practical differences. In the beginning, when I was making television, everything was live, you shot and broadcasted the thing simultaneously. At that time, there was continuity, the work couldn’t be interrupted. Then, when magnetic videotape arrived, we could work more calmly, piece by piece. Very similarly to cinema.

But in both cases you need to make an image. I mean, the image must be significant, it must give an atmosphere, explain things, help the actors. This happens whether in cinema or in television. In both cases there’s the lens, and in both cases there’s the image.

Most of the differences are of a psychological nature, let’s say. It’s worth noting that cinema is seen on a big screen, in an auditorium; there’s a gathering of people, something that comes from theater and which is fundamentally a religious fact. While television goes to your house, under a light that renders visible to us the natural quotidian environment that surrounds us. So, film’s penetration seems to me more violent but also, at the same time, how can I say it?, more anti-Brechtian. Film offers the dream, alongside an easy identification with a positive character. That explains the success of films where there are goodies and baddies. You identify with the goodies and you hate the baddies. In all cases, the baddies either die or get killed, while goodness and our hero triumph. At home, the dream isn’t as strong because it’s too much in tune with the rest of our everyday lives.

So, from the point of view of morality, that is, of the message, I’d say television has a stronger capacity for penetration than cinema, precisely because the TV spectator endures: when he starts watching a show, he must make an effort to move and change the program if he wants. Nowadays with the remote it’s easier, but when I used to work you needed to get up, tune into another channel... But if the spectator moves on to another program, a part of the program he abandoned has already touched him. Perhaps, something will remain. Therefore, from the point of view of educating the spectator’s taste for a greater sincerity of sentiment, for a greater social consciousness, for many things, television has greater pedagogical and penetrative possibilities in regard to cinema, because in cinema refusal happens first, by not going to see the film. While in television, refusal happens during, sometimes after the film. There is a resistance, so to speak.

JG: Given we’re talking about it, I have the impression the line dividing television and cinema will be getting thinner and thinner. While you were shooting Maria Zef, did you pose to yourself the problem of making a film that would be shown both in theaters and on the small screen?

I hope that in France the film is seen in theaters. I find the close-up to be the normal means of television communication. Because, as I’ve said many times before, in television the size of a close-up matches the physiological dimensions of man. My face, compared to a close-up of it, is identical: 35 centimeters when you see it on a screen and 35 centimeters for whoever is looking at me. In other words, it’s a dialogical stance.

In cinema, the close-up is something terrifying, something looming over us with all the hairs, pores, all of that, you see everything! In cinema, the close-up must be used somewhat sparingly. For me, it’s precisely the abuse of TV-style close-ups that ruins so many films, from the point of view of their construction: an excess of close-ups no longer means nothing. Close-ups that are repeated, repeated and repeated, they lose their charge, the expressive strength they’d have if they were less abundant. It’s not an aesthetic, but psychological matter, and it must be taken into consideration.

While making Maria Zef, I was very careful not to make too many close-ups if they weren’t adequate or if they weren’t necessary. It’s worth saying that, for me, I shot a film for the cinema that was then broadcast on TV. I’m not sure if you would agree...

JG: I absolutely agree, but I wanted to say that nowadays it’s much more easily accepted to see on TV a film with few close-ups, perhaps because people watch more and more films on television. At the end of the day, I get the impression that the cinematographic aesthetic has prevailed over the television aesthetic.

Yes, and that’s a blessing. First it was television who was prevailing over cinema, also because many American directors who made successful pictures came from television. And so, they exaggerated a little bit with the close-ups.

Besides that, something that really annoys me are the ad breaks. And, unfortunately, there’s a kind of cinema that is perfectly suited for having ad breaks. Most films today have an advertisement style, in their rhythm, in some camera movements, in the composition of the shot. Even in the colors, in the lighting effects. This really bothers me.

FJ: What filmmakers do you admire the most, in Italy and in film history in general?

I had a great love affair with Pasolini. I can’t say this love has been turned into hate, but it has certainly cooled down after the last film he made. Among foreign directors, I really like Buñuel: I really admired his first films, but the more he made, the more I liked them. One of his last films, La voie lactée, to me is an absolute masterpiece. In La voie lactée there is this fusion between metaphysics, religion, sentiments, human relations and a story with an extraordinary epic afflatus. It’s the only epic film of our times. Even the episodic structure is typical of the old epic of great Greek poetry.

I'll stop here, otherwise I’d cite too many names. Too many, because every time I see a film, even when it’s a rather bad film, I can see the effort, the labor, the problem-solving required for reaching a result that may be mediocre but which is the result of human effort, of suffering. It strikes me so much that I can never wholly despise a film. I say, ‘It may be bad, I don’t know, but you can see the effort of trying to make something, to get to a result.’ It moves me, sentimentally. So I’m a terrible judge, always ready for forgiveness.

I can tell you that I recently saw a film by King Vidor, 1928’s The Crowd. No film today reaches that level, that beauty and that truth, without a single word, just intertitles. In the Italian version, the intertitles were bad.

JG: We may conclude with a final question: can you tell us about your film project based on Pavese, Il diavolo sulle colline?

It’s part of the melodramatic lineage. It’s an almost contemporary story. It takes place in 1949, that is, four years after the end of the war, at the beginning of the economic boom, when the youthful hopes born out of the Resistance hadn’t materialized. People were reentering the ranks of a more or less corrupt, oldish society. It’s the story of the slow crisis of four young men who are slowly reentering these ranks.

It interests me because I think the crises we have today are very similar to the crisis of conscience that happened after the war. I have the impression that the real illness of our century, of our times, isn’t so much the economic or political problems, but our absence of morality. Men have lost their sense of values. People talk about a ‘crisis of values’, but all centuries are filled with crises of values. There isn’t a single epoch when man hasn’t gone through a crisis of values.

But it’s precisely in these crises that man’s primordial values are saved. The primordial value of man is mercy, the Romans’ caritas, or the Christians’ charity. That is the fundamental value of man. It’s man faced with others. Mercy. It’s not a material thing, it’s a spiritual thing, a relation to God. Men must recognize each other thanks to this divine spark of theirs. The other fundamental thing that’s lost is remorse, man is losing yet another typically human quality. Man is different from animals because animals have no remorse. Man knows remorse, and if he relinquishes it he becomes a kind of animal, more animal than he already is. That’s why I say that, in a crisis of values, we must keep our fundamental values close, and the others shall follow them. So, the crisis of today, more than economical or political, it’s a human crisis of the loss of values. And this devalues man, because he loses his own values. Our currency is losing its value, and so is man. Man must somehow reconquer his morality, whether it be a Kantian universal law or the moral code of a savage tribe that states that ‘you must kill the man from the neighboring tribe…’. Because that too is a value. And we’re losing all values.

Even criminal values no longer have any meaning. Nowadays, crimes are committed without human participation, almost without any pain. Whether for the criminal or for the victim, there is a physical pain alongside a moral pain. But criminals have lost their sense of suffering. If they commit a crime and they suffer for having committed it, that’s already a kind of morality. In short, we're moving on to very difficult problems...

FJ: I know that filming for the Pavese picture should be starting in September. Have you already cast the actors?

Yes, I do intend on starting it in September. No, I don’t have the actors yet. I’m hesitant about using professional actors. Given they’re eighteen- to twenty-year-olds, maybe I’ll once again try to use non-professional actors. As long as I have the same luck and that I’m capable of finding performers as good as those in Maria Zef.

FJ: This time, Siro Angeli is not writing the screenplay. Do you have other collaborators?

At the moment, Angeli is writing a very interesting novel. I’ve written screenplays without him, with other collaborators. I always have some collaborator, because the screenplay and everything that a film is made of is the fruit of collaboration. To me, the man who does everything himself isn’t suited for cinema. He may be an artist, a very personal one, perhaps even a genius, but the cinema-machine is a collective machine made out of several workers who aim at the same goal, at the same result.

This interview was recorded in November 1982 at the Luxembourg Cinémathèque, then directed by Fred Junck, on the occasion of a retrospective series presented by Jean A. Gili. This tribute to the filmmaker opened with a preview of Maria Zef.

Le fatiche di un pigro, in Ai poeti non si spara: Vittorio Cottafavi tra cinema e televisione (Edizione

Cineteca di Bologna, 2010), pp. 108-120. Translated from French to Italian by Altiero Scicchitano.