There is, of course, no a priori reason why a historical spectacle film should be boring, or risible. But most of them are. The details are too familiar to need analysing.

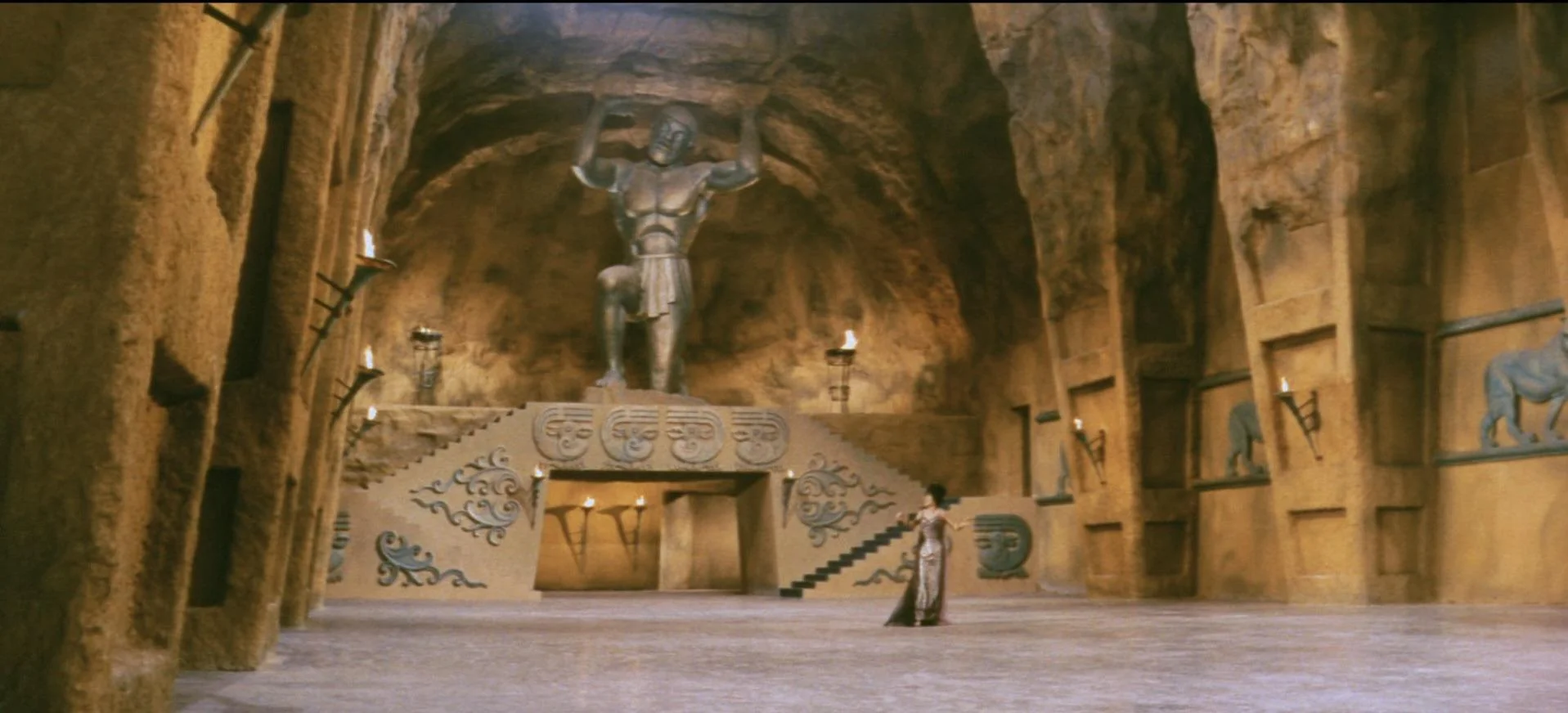

However, Hercules Conquers Atlantis has neither the shoddiness of the normal run of Italian spectaculars, nor the deadness which seems inevitably to afflict, in part or in whole, the careful, expensive, luxury model. In direct contrast to Cottafavi’s previous Hercules film, Vendetta di Ercole (retitled in England, for some unknown reason, Goliath and the Dragon), it has a clear story-line, excellent colour, good sets, acting and music, and abundant resources. Cottafavi doesn’t have to waste his energy on trying to make half a dozen palsied extras look like a massive invading army. In fact, Atlantis is invaded, and conquered, by three men and a dwarf, which is an economical way of doing it. But the resources are there when needed and enable Cottafavi to achieve a series of stunning visual effects: a chariot drawn through underground passages by a team of white horses; the extraordinary violet colour of oars dipping into the sea; a massive final sequence of Atlantis disintegrating.

However there is more to the film than what Mr. Billings in Kine Weekly calls its ‘staggering staging’. Here one comes up against the false problem of the good genre and the bad genre. Audiences are conditioned to think that a film with a title like Hercules Conquers Atlantis can’t be more than a pleasant bit of nonsense. How can it have meant anything to Vittorio Cottafavi, who is an intelligent, sophisticated man and directs prestige productions for Italian TV (Dostoievski, Sophocles’s Antigone, etc.)?

One could be misled, by thinking in terms of the strip-cartoon, into thinking that Cottafavi is parodying a genre that he despises. It is true that there is no exhaustive ‘characterisation’; but in this the strip-cartoon differs little from the fable. By going back into the past the artist can recreate a simpler, purer world free from mundane associations. A parallel that suggests itself is Yeats’s adaptation of Irish myth in his early poetry: for instance, the death of Cuchulain (Three days he struggled with the encroaching tide / Then the waves flowed above him, and he died). It would be equally apt, and equally meaningless, to condemn this for its simplicity, which is if you like that of the strip-cartoon, but is also that of the fable, the myth.

Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide (Vittorio Cottafavi, 1961)

Admittedly, there is comic relief, supplied by the dwarf, and Cottafavi’s treatment of Hercules himself is unaccustomedly humorous. However, this humour is perfectly consistent with the film’s presentation of heroism. Hercules would rather finish a meal than join in a brawl, he’d rather sleep than fight, he wants to stay at home instead of joining the King of Thrace’s expedition against Atlantis. The king has to drug his wine to get him on board ship. They all watch him apprehensively as he sleeps on. But when he wakes he just looks round, sees what has happened, and smiles: ‘Lovely day, isn’t it?’

He will only fight under provocation, in defence of himself and his friends. Atlantis has to be destroyed since otherwise it will destroy Greece. Atlantis represents an earlier stage in creation, the era of Uranus, who in the battle of the gods was defeated by Zeus. Antinea, the Queen, is training a race of supermen. She still has magical powers which she tries to use against Hercules (cf. Odysseus and Circe). The core of the narrative is this conflict between the old and the new order. Antinea shows Hercules supernatural tricks; he replies that the Greeks are satisfied with Nature as it is. ‘I believe in what I hear and what I see.’ Finally, he destroys them not by strength, but by strength combined with intelligence. Magic yields to the new Greek ideal of the kaloskagathos.

This is worked out with direct, elemental imagery. The vestiges of supernatural power in Atlantis come from a rock in the mountain, formed from a drop of the God’s blood: ‘a rock that gave Light and Darkness, Good and Evil’. After prodigious feats of strength and cunning, Hercules enables the rays of the sun to fall on this rock. Then is fulfilled the prophecy of the island’s destruction, which Hercules was ‘fated’ to achieve.

I’ve summarised the plot to show how, without in itself being ‘good’ or ‘bad’, it makes a perfectly meaningful framework within which Cottafavi can work. And he realises all its epic possibilities — I won’t say by his use of the Super Technirama screen, because he doesn’t work in terms of the sort of composition that implies; but by his organisation of material within it.

Its scope helps him to capture the essentials of a scene in a single dynamic movement: the camera moving down between two cliffs, showing the sand below, with the men streaming out across it, and the boat and the sea beyond; or tracking down from the boat’s sail to reveal the men, surrounded almost tangibly by sea and sky. These shots have a force which goes beyond the purely pictorial: they impart a heroic scale to the narrative, without in any way imposing on the reality of the scene. And there is a more direct, if indefinable moral force simply in the way Cottafavi shows the pit into which the weaklings of Atlantis are cast, and the ceremony where the élite children are led away to be trained into supermen.

There is no real English equivalent for the word dépouillement, which one really needs here. It implies the stripping away of everything irrelevant or distracting, of preconceived associations. Jacques Joly said of Walsh’s Esther and the King: ‘les personnages n’existent que dans la mise en scène’ [‘the characters exist only in the mise en scène’]; and in Hercules Conquers Atlantis the form is, more than ever, indistinguishable from the meaning. At certain moments Cottafavi succeeds in expressing states of mind, emotions, conflicts, with an extraordinary purity, in crystallised form as it were. The nobility of Hercules, or the helplessness of the young girl, Ismene, appealing for mercy. And in achieving this sort of purity, the much-maligned genre is not a hindrance at all, but an inspiration.

In Movie, 3, October 1962, p. 29.