Straub with Bach, Paradjanov with Sayat Nova, Lang with the Nibelungen, Mizoguchi with prostitutes, Ozu with Setsuko Hara’s eyes, DeMille with the Bible and Rembrandt, Ford with peasants, horses and soldiers, Costa with Vanda and Ventura, Warhol with the Empire State Building and John Giorno, Cottafavi with Tchaikovsky and Dostoevsky... In a night of shadows juxtaposed with beams of blinding light, a woman’s soul seems to project itself in a unique movement that prolongs the continuity of her emotions into the horizontal and vertical lines of a brickyard that encloses the path that she, alone and still a prisoner of herself, agrees to endure, crestfallen, under the sign of shame: she has just murdered her ex-lover, a renowned pianist, after an episode of hallucinatory emotional coercion instigated and accompanied by the execution of the Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1 in B Flat Minor.

What does a filmmaker do in a moment like this?

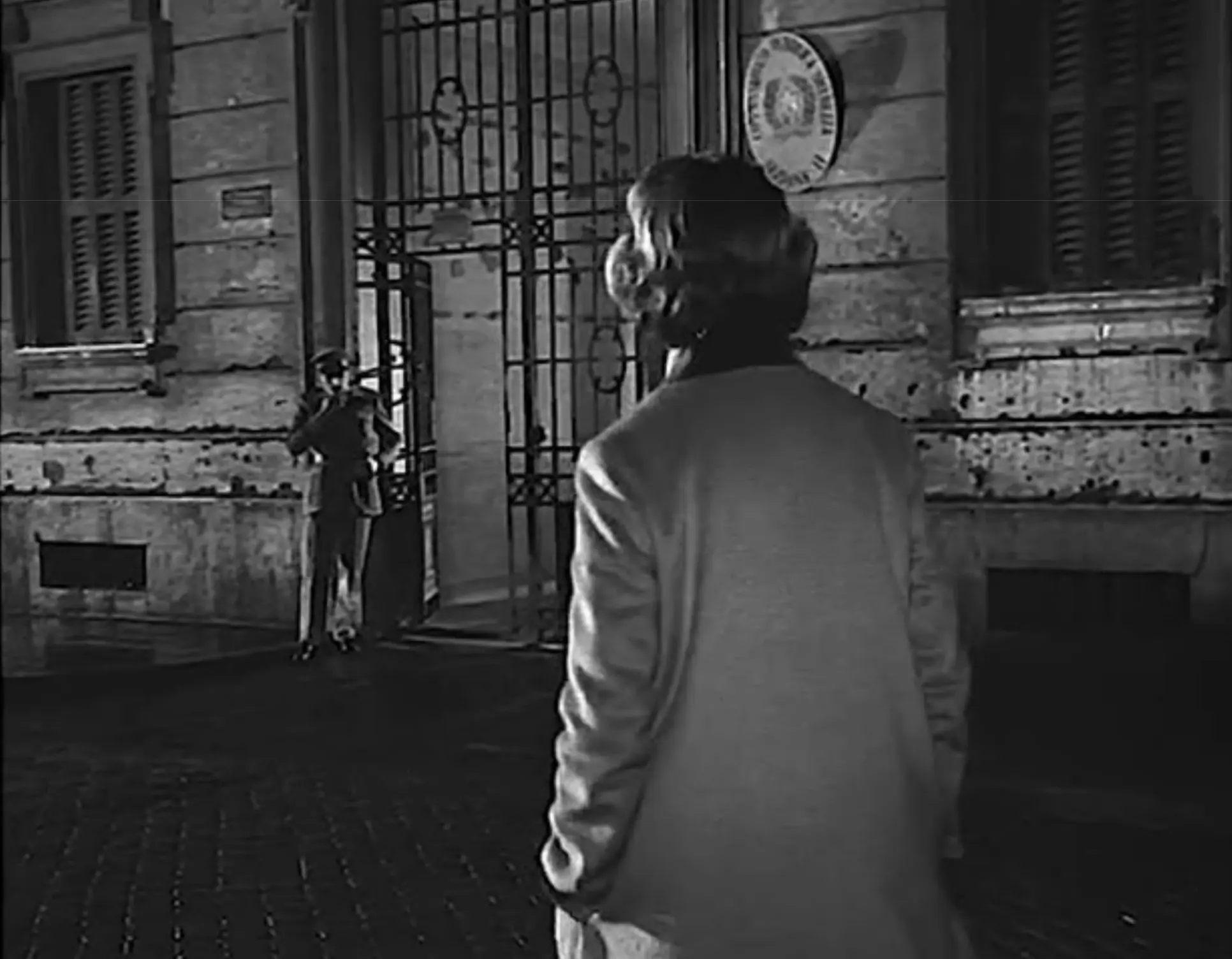

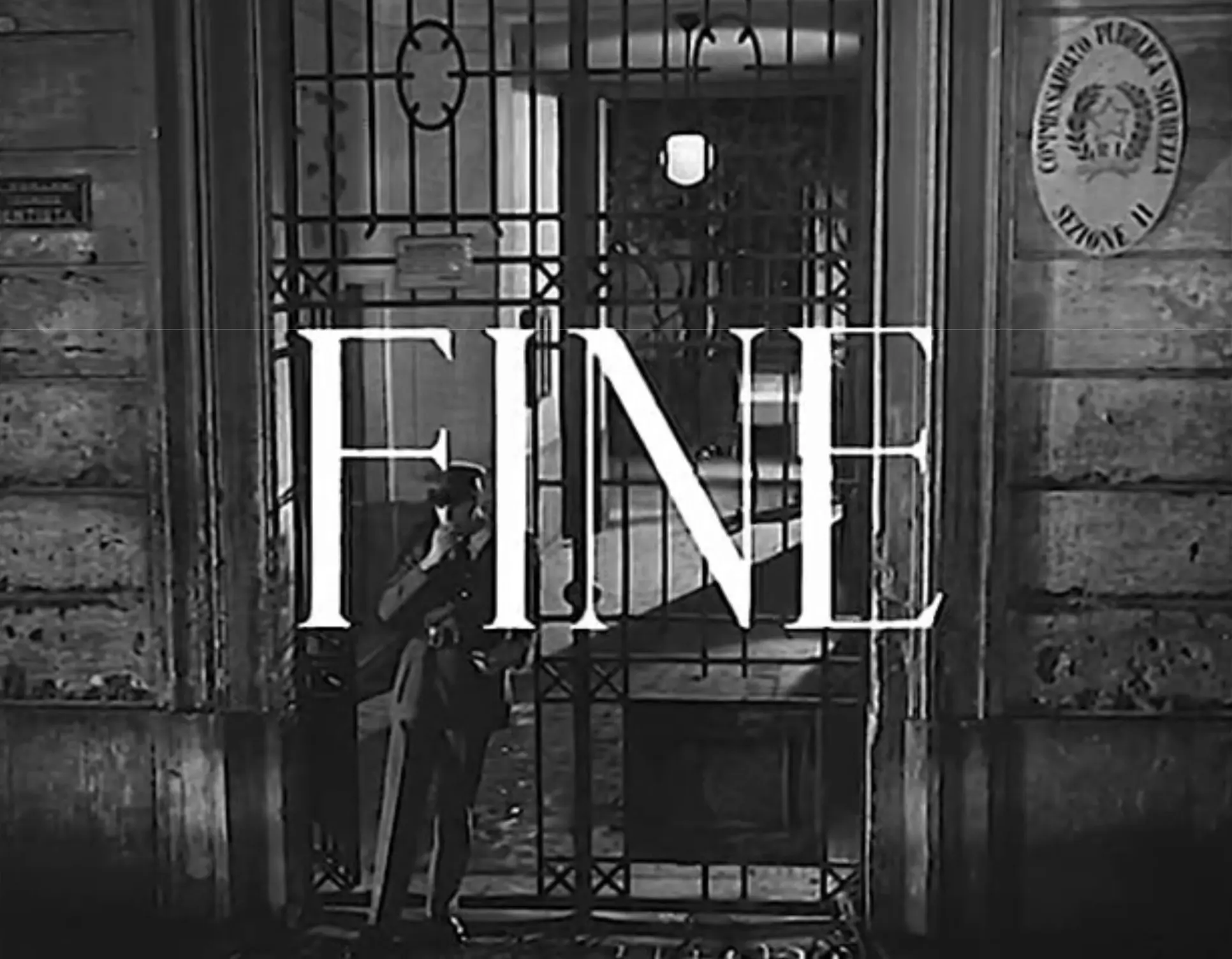

Little, that is, a lot; more precisely, everything: a nape; a conventional hairstyle from the 1950s; an angle that accentuates, in an unexpected perspective, as in De Chirico, the slope of the humid courtyard over which this woman picks herself up again, body and soul together in the same movement. Almost distressing moment of the pain of self-acceptance, a moment that Cottafavi dynamizes in an unbelievable vertical movement of the camera, from top to bottom, which not only rebalances but lightens all the geometry of the physical space of the action, whose Euclidean conclusion projects this woman’s body literally to its freedom, like a bullet projected through the barrel of a revolver, there at the gates of a police station; a resolution that Tchaikovsky’s music sublimates into a feeling of plenitude that everything seems to indicate represents the encounter and complete fusion of a life with its destiny.

Art, aristocracy of the soul: nobody could have done better with so little, and indeed nobody did.

(May 15, 2013)