What delivers me from the anguish into which an unrestricted freedom plunges me is the fact that I am always able to turn immediately to the things that are here in question. I have no use for a theoretic freedom. Let me have something finite, definite matter that can lend itself to my operation only insofar as it is commensurate with my possibilities. And such matter presents itself to me together with its limitations. I must in turn impose mine upon it. [...]

My freedom thus consists in my moving about within the narrow frame that I have assigned myself for each one of my undertakings. I shall go even further: my freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles. Whatever diminishes constraint, diminishes strength. The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees oneself of the chains that shackle the spirit

—Igor Stravinsky, Poetics of Music

I

It would not be incidental to extend the analogy between music and cinema as a concrete demonstration of the compositional aspects that permeate the work of Vittorio Cottafavi. In his case, the use of such a figure of speech would not arise in critical analysis merely as a poetic device, nor would it be limited to the exploration of relationships that are already well established, such as the correspondence between timbre and color when transposed to the realm of pictorial and musical relations, or the often tenuous comparisons that sought to associate each musical note with a kind of color or visual tone. What is at stake in the transposition of a certain transdisciplinary vocabulary within this text is the structural understanding of a proper notion of harmony, particularly of a predominantly classical harmony, that runs throughout the filmmaker’s career.

This comparison refers not only to the musical domain but also to the Italian director’s first failed attempts at entering the world of the arts (in an interview given to Michel Mourlet in 1961 for the magazine Présence du cinema, Cottafavi reveals the failure of his early ventures in literature and painting before arriving at cinema). More importantly, it underlies his very notion of mise en scène as the true transposition into cinema of a harmonic notion per se, with the subordination of the horizontal arrangement of elements (and therefore of the various ‘voices’) that make up a filmic work — sound, décor, montage, screenplay, cinematography — to the verticalized combination and conjunction of motivic needs and their subsequent development.

II

Muss es sein? Es muss sein!

—Ludwig van Beethoven

In Cottafavi, the filmic motif is introduced in a crystal-clear manner in the first moments of the film. There is an orthodox submission to a genre: whether it is melodrama, peplum, or science fiction, a familiar pattern reaffirms the viewer’s expectation of how the initial premise will develop, yet this clarity does not ultimately lead to a predictable outcome. Since Cottafavi is endowed with a remarkable capacity for tension and release, for suspense and resolution, it is precisely through his perfect mastery and skillful management of classical conventions that the only possible resolution to the presented tension can appear as the least expected.

Let us consider the beginning of Nel gorgo del peccato (1954). ‘I had two children. I had... I have two. A mother is never separated from her offspring, even when she departs for a good reason.’ This is the statement made by Margherita Valli — the character played by Elisa Cegani — in a voice-over set against a panoramic shot of clouds. We still do not know the reason for her departure, why she speaks in the past tense, nor the reason why she would have reluctantly shied away from her maternal vocation. Yet this statement persists as an obsessive idea throughout the entire film. For immediately afterward, we are introduced to the drama of Alberto, the prodigal son, who, after a period of estrangement that has included forays into the criminal world, returns to his mother’s home, bringing along his wife Germaine a few scenes later.

In our hermeneutic projection, we believe we have understood the meaning of Margherita’s words, and as the narrative unfolds, this suspicion seems to be confirmed at every moment. When Alberto and his wife start to live under the same roof as his mother and brother, his wife’s meanness is signaled: she is contemptuous of poverty, flirts with easy money, and constantly clashes with the values passed down by Margherita’s maternal inheritance, which contrast with her detachment as a modern woman of the city. In these characteristic contrasts that affect the melodrama, we sense the possible reason for the sentence uttered at the beginning of the film, even though complete adherence to the proposition mentioned is made impossible by a factor that escapes reasoning: she also refers in the past tense to Alberto’s younger brother, whose function in the plot is only to accentuate her need for the male presence of his older brother in the family home.

This suspension does not prevent the initial motif from logically unfolding throughout the narrative. Variations on the same motif and problematic responses to it permeate the plot: Alberto finds work in a garage; his wife grows dissatisfied with the meager earnings and the conflict escalates. A former criminal associate appears at his workplace, offering once again an alternative path, but Alberto, firm in his initial decision to remain honest, refuses it. Upon learning of Filippo’s presence, Germaine is seduced by his proposal and, unable to adapt to Alberto’s new life, leaves in search of easy money. Unjustly blaming his mother who had accepted her daughter-in-law’s temperament with resilience and sanctity, for Germaine’s departure, Alberto starts living with his wife, returning to the easily obtained money; the problems mount when this former accomplice tries to incriminate him in order to steal his girlfriend, in a clash that eventually culminates in her being seriously injured.

With Germaine in a coma in the hospital, the blame naturally falls on Alberto and, to save her son’s face, it is Margherita who goes after Filippo in order to demand that he explain himself to the police. She is the one who dies to save him. Even though we become aware at that very moment that Germaine had already regained consciousness, rendering Margherita’s sacrifice seemingly useless. Later we hear the same voice-over narration, now during a scene that brings together Alberto, his wife, his brother and his friend in a family reunion, with Germaine now adopting the maternal role. In an equation diametrically opposed to that of Teorema (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968), it was Margherita’s saintly renunciation and her departure from the scene that allowed the order of the elements present in this system to realign itself.

The narrative solution found here is remarkably similar to that of Time Without Pity (Joseph Losey, 1957), a film endowed with a competence in internalizing classical conventions analogous to that of Cottafavi: no matter how logical the development, we are still surprised by how the note achieved is the only note that was possible within the film’s system. And this surprise does not stem from the narrative prowess of Giuseppe Mangione’s screenplay, based on the novella by Oreste Biancoli (although the filmmaker’s choice of this source material certainly reflects the worldview that permeates his cinema). Rather, it comes from his ability to find precisely the only possible cinematic solution to the problems posed by the unfolding of the work as a dramatic unit, by the mastery with which he allows everything to happen the way it should, through the refinement and synthesis of its most essential elements. There is, therefore, an erasure of the filmmaker’s presence, a transparency of the montage: we do not feel his hand or his touch at all, and we anxiously await the natural sequence of events, which does not prevent, and on the contrary accentuates, the surprise.

This is also why Cottafavi’s cinema has been described as a cosmic symphony. This thesis is reinforced by the panoramic shot that opens the film. If the presentation of spatiality in the opening minutes of certain films serves to geographically demarcate the setting where the confrontation or reintegration of individual and environment will unfold, it is no coincidence that Cottafavi chose a space symbolically associated in Western culture with Paradise: the sky above our heads. This is also the point at which the work concludes: it is true that in the final sequence, Margherita’s voice does not initially appear juxtaposed with the ethereal dimension of the clouds, but with the concrete domestic space where the action unfolds. Yet soon afterward, as the camera pans across the characters within the scene, as if our gaze was searching for the speaker, it avoids Alberto and Germaine’s dance toward the window, and with a sharp cut Cottafavi now directs us, by means of a panoramic shot, from the outside of the concrete world, with its streets and blocks, towards the sky once more.

The clash or reintegration does not unfold, therefore, within the realm of material or even ideal forces operating in the real world, but rather in the realm of metaphysics, and of the reintegration of man into a spiritual order. Through the finitude of a work of art, Cottafavi inserts the infinite. And yet, ambivalently, he does not achieve this through Romantic sublimation; rather, it is within the domain of concrete generality that Cottafavi’s metaphysical drama takes shape. Or, in Rohmer’s terms regarding music, it is sustained by a harmony that is ‘itself the product of the laws of nature’. Or, to put it differently, ‘this question has a content, but the content is the question itself, the act of questioning, the pure questioning.’ [1] Must it be? It must be!

III

Music proves to be fruitful as a metaphor precisely because of its harmonic verticality, which is also present in cinema. However, while in music this verticality arises from distinct instruments or voices combined or juxtaposed, the tools of cinema intersect more in the process of production than in that of execution. The result, in theory, is the same once the work is completed, but during its preparation a film director must combine the task of composer with that of conductor: organizing and instructing how each instrument must perform its part within the overall structure, thereby also assuming the challenge of performance.

If the verticality factor were not involved, the analogy would be effective only when drawn between the narrative aspects of a work and its development; that is, their inevitable affinity, given that both arts unfold over time — a proximity that they share, though somewhat less rigidly in terms of predetermination, with literature. There would not be much more to discuss, other than the melodic line, that is, the fact that in Cottafavi’s cinema there is full linearity and an aversion to abrupt jumps. His cinema always moves in a defined direction, avoiding both elliptical narrative rarefaction and the prolongation of tension. In short, there is no fragmentation of the melodic line, as in Resnais, nor an extending of nuances, as in Rossellini; his opposite would perhaps be Antonioni, where both elements — narrative fragmentation and the prolongation of the gaze under a given sequence — meet.

Evidently, such comparisons are not evaluative in nature, and serve to delimit the aesthetic spectrum in which his cinema is situated. Thus, it is through harmonic verticality and texture that a more complex comparison becomes possible, offering more data for a more comprehensive understanding of the spectrum. If this cinema involved a combined contrast between sound, space, and narrativity, he would be called Orson Welles; if dissonances were more frequent, whether more or less calculated, he would be called Godard; if it were predominantly contrapuntal and less homophonic, he would be called Marguerite Duras. But Cottafavi’s cinema contains neither the combined contrast between sound, space, and narrativity, nor calculated dissonances, nor a predominantly contrapuntal character. His cinema lies not only within a full and coordinated alignment of every manifested cinematic component, but also in complete adherence to dramatic unity.

Because they are embedded in an aesthetic that does not demand attention to its most apparent formal devices, these qualities often go unnoticed by a less trained, attentive, concentrated, alert gaze. It was necessary for Michel Mourlet to advocate for these invisible cuts made ‘in the amorphous mass of reality’, or for this adherence to dramatic unity through the ‘selection and juxtaposition of essential shots, like a gaze that would always go straight to the crux in the course of an event’, for such impalpability to become tangible, for the economic and synthetic elegance of refinement to finally be perceived. [2] And it is because of this conscious handling of classical forms that Cottafavi’s cinema is less that of an inventor or a creator than that of a master. It is through self-assurance and possession of a comprehensive repertoire capable of finding ingenious solutions within the narrowest of needs that the fruit of this conscious formal construction appears to be immanent, natural, given. Everything seems magical when one does not understand the artifices of an illusionist; it is only when those devices are exposed that the ingenuity of the operation is recognized.

This does not mean that the body of his work is endowed with relentless rigidity or orthodoxy in its components; there is a volatility in the ways his principles are applied, arising from the vast repertoire of cinematic possibilities possessed by these craftsman’s hands. As previously stated, his cinema does not make abrupt jumps in its melodic line, but this does not mean that ellipses or temporal transitions do not exist; rather, when they occur, they are interwoven with recurring motifs that develop chronologically within the work, without transposing these moments outside of their dimensional unity.

Fiamma che non si spegne (1949) provides us with an example in which the passage of time imposes a narrative progression that must be agile in order to cover the trajectory of father Giuseppe and son Luigi. At a certain point, the narrative focus must shift from one to the other, demanding a power of condensation and synthesis that could potentially obscure the desired clarity. Yet, quite to the contrary, it is reinforced by the unity signaled through the modulations presented by Cottafavi in the transition from the first to the second half of the film, through certain themes that are repeated and revisited; at no point does the flow of lived time itself end up driving the narrative.

For this reason, although Fiamma is endowed with a much stronger structural necessity than his other films — at a certain point the son’s trajectory must catch up with his father’s — it cannot be said that it is properly baroque. We know that Cottafavi was inspired by Bach when making some decisions within the final sequence, but the filmmaker understood the analogy with Bach’s severe counterpoint as a matter merely of the alternation of shots, when in fact classicism in cinema appears linked to a broad structural aspect of the work (which may involve both the interplay between various cinematic ‘instruments’ and the many voices of just one, as in the baroque organ).

Another paradigm of this malleability lies in the ease with which Vittorio Cottafavi navigates, in Vita di Dante (1965), three distinct possibilities (classical staging, realist depiction, and montage) without these devices turning into either a naturalistic subtraction of refinement or a modernist pursuit of structural experimentation. On the contrary, the use of these procedures seems to confer homogeneity upon the film, without lapsing into the vices of eclecticism. The cohesive force of the film even manages to establish a passage of different literary genres (from anatomy to testimony or confession) without the loss of filmic unity.

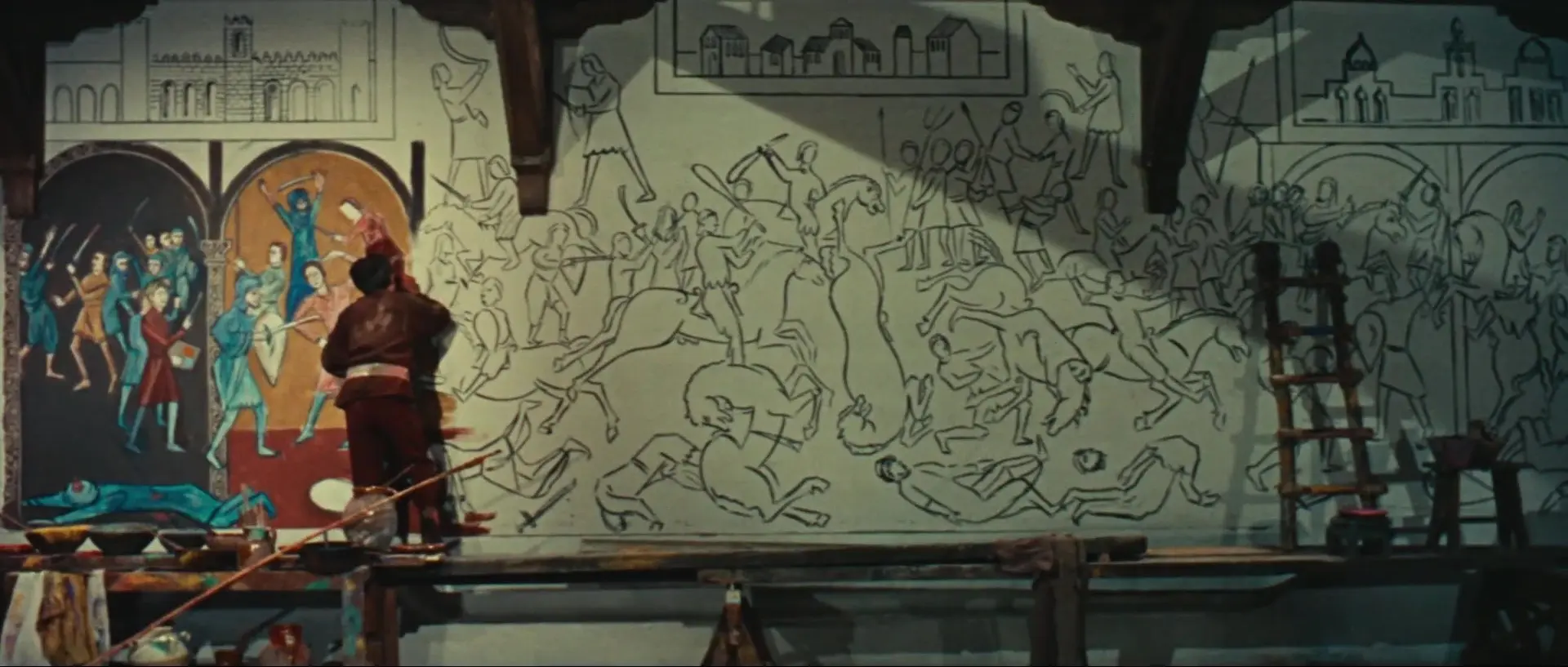

As a researcher, Cottafavi carries out a historical examination of thirteenth and fourteenth century Florence not only through the representation of its graphic inscriptions, drawings and engravings, maps, coats of arms, coins or historical documents (with a much broader grasp than that of a mere illustrative scope, thanks to a rhythmic use of editing — which is at once discreet and absorbed into the narrative — and to a camera that scrutinizes such testimonies) but also by articulating more than one narrative layer. This articulation encompasses, in addition to Dante’s personal life, a comprehensive panorama of the city, with its personalities, intrigues, wars and repercussions in Rome or in other Italian cities of the period (which even allows him to use Giotto as a character in order to carry out this transition between the film’s numerous levels).

From anatomical description, Cottafavi frequently moves to testimony: the gaze that captures epiphanies, so familiar in Rossellini, is made explicit here through low angles of monuments, through shots of the Baptistery of Saint John, through tracking shots in Dante’s house, through the superimposition of layers that juxtapose zoom-ins with zoom-outs in interior spaces, through four distinct camera angles that, at a certain point, converge on the poet’s face, through the observer’s gaze that avoids cutting when moving from a wider shot to a close-up — in a testimony that does not settle for naturalism but is instead enhanced by the contours of an elegiac imagination. This imagination manifests itself in reveries where Cottafavi directly intervenes in the frame by superimposing the bodies of Dante’s companions in zoom-out against architectural spaces in zoom-in.

The film, however, does not unfold solely in this third-person perspective, and at times resorts to confession to achieve its aims: the historiographical and pedagogical commentary gives way to Dante’s own narration, through his observing gaze, in a precise cinematic application of free indirect discourse. With such skill, Cottafavi not only coordinates these three narrative strata satisfactorily but also intertwines them within distinct temporal structures, moving from a time in which Dante’s beloved and many of his friends are already dead to subsequent depictions of sequences that precede those events, without any ellipsis and without any need to verbalize this passage in a redundant or tautological way.

In the sequence following Beatrice’s death, for instance, Cottafavi establishes within two minutes a complex maneuver in which external shots of bell towers (which seem solid at first glance but actually contain a subtle camera tremor typical of those who capture epiphanies — a recurrent motif throughout the film) shift to more specific and intimate shots: freeze frames of a now-deceased Beatrice, amplified in a homophonic manner by Dante’s voice in first-person reciting ‘Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare’, from La Vita Nuova. This voice persists until the recording of the funeral procession, which concludes the sequence. In the procession, the static image of a living Beatrice gives way to the representation of the dead body in a longitudinal movement that follows the nuns on the right, passes to the obtuse angle of the observer and culminates in the one who watches (in a gaze that turns, therefore, to Dante). With just three shots, Cottafavi not only resolves in an economical and synthetic manner the centripetal needs of the narrative axis through a rigorous staging, but also moves through other compositional alternatives in an exact and rigorous manner (but also sweet, graceful, pleasant), challenging any notion of a more dogmatic ontology.

Sequence following Beatrice’s death in Vita di Dante.

Curiously, Cottafavi absorbs all this interweaving of multiple directives through clarity and simplicity. His skill does not stem from employing hermeticism or labyrinthine syncretism but from using these devices in an exceedingly simple manner, perfectly aligned with the most basic necessity of telling Dante’s life story: to travel through the public spaces where he walked; to recreate the private places where he suffered, wrote, and rejoiced; to reconstruct the clothing, dances, battles, and cavalry charges of his era; to provide the factual data; and to position him as the objective result of a historical equation, while at the same time subordinating all of this, now and then, to the prismatic voice of the poet himself, who recites this act of living within time — absorbing and channeling this universal dimension into the particular.

IV

Depth and simplicity are connected, in the realm of rhythm as much as in that of harmony

—Éric Rohmer, De Mozart en Beethoven

The shot can be described as the minimal rhythmic unit in Cottafavi’s cinema. It initially emerges in a ‘danced manner’, as a mixture of storm and stress, unafraid to ‘strike the cadence in an open and almost childlike, primary, limited way’. [3] Il boia di Lilla – La vita avventurosa di Milady (1952) is Sturm und Drang par excellence: here, there is an impulsive emotiveness, though still controlled by form; there is an exclusive preference for shot/reverse-shot over the pursuit of diagonal depth; and the sequence is fragmented into minimal units that repeat in the swiftness with which it moves from one beat to the next. In this way, Cottafavi does not seal off the possibility of a classical ‘window to the world’, but rather mediates this relationship with nature through conventions, distancing himself from testimony and drawing closer to a gravitational pull inherent to the needs of the narrative, avoiding both the self-consciousness of formal aspects or their erasure by the act of mere recording.

It is through the narrative’s internal laws that Cottafavi approaches the reality behind each gesture and, in a deductive manner, reaches a ‘harmony of the universe’. Through the framing of a city, a painter might, by analogy, demonstrate universal order. However, for it to exist within a sequence, the strength of its rhythmic unity imposes the cohesion necessary for this line of reasoning not to be lost to an inattentiveness that could arise from drawing attention either to the discourse itself or to its subject. What we encounter here, however, is a symbiosis of reality mediated by language, but not an artificial reality, nor reality as a register, but rather reality permeated by Cottafavi’s usual necessity of enchantment.

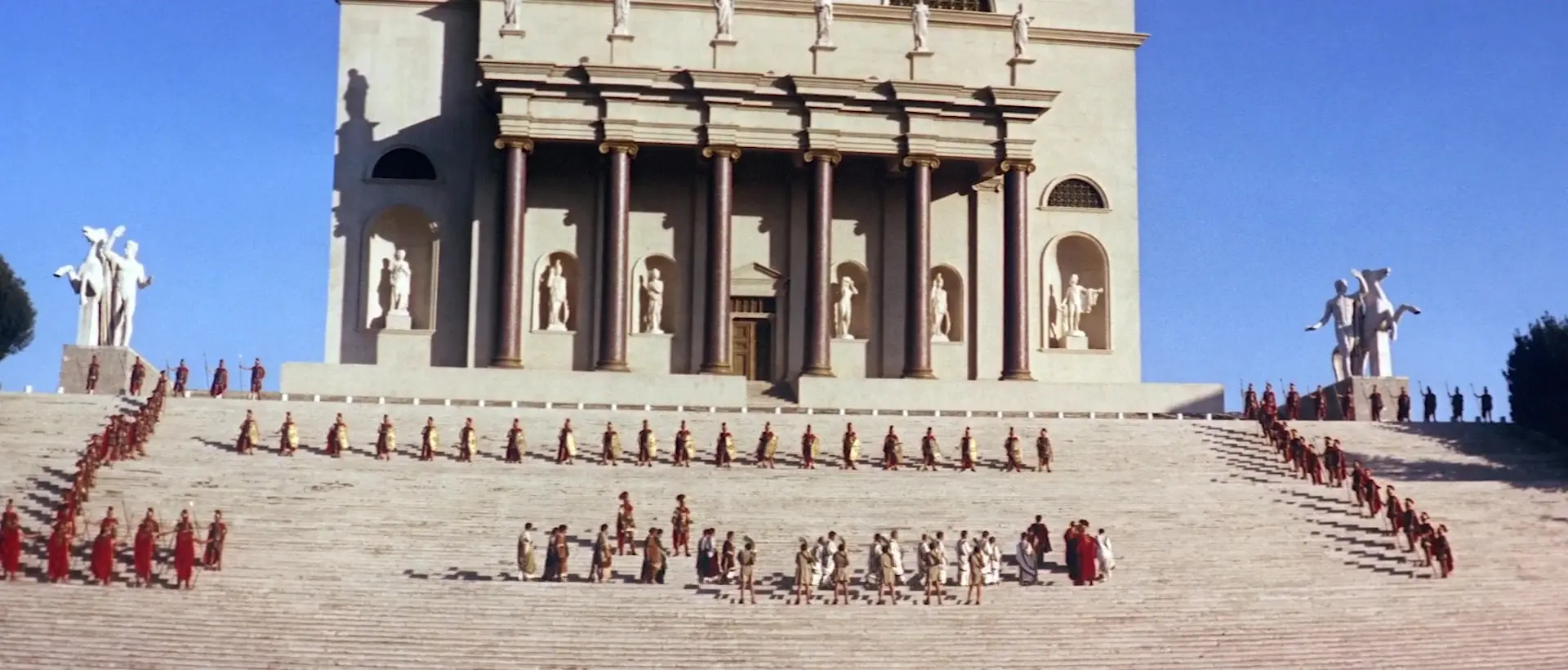

If Cottafavi’s presto is Il boia di lilla, his allegri are, for the most part, his pepla: Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide (1961), I cento cavalieri (1964), and Messalina Venere imperatrice (1960). In these films there is a lightness marked by a breaking up of the sequence into quick, deft shots; and because the sensibility here is more controlled and measured — thanks to the use of diagonal compositions and a more even distribution of bodies in space — a greater rhythmic rigidity also emerges. At this point, his cinema no longer poses a question. Or, to borrow Rohmer’s words about Mozart once more, it becomes ‘an affirmation as such, a “yes” repeated insistently’. [4] La rivolta dei gladiatori (1958) would be the ‘yes’ superimposed upon concrete necessities, but even so, it is a dialectical ‘yes’ — a ‘yes’ so absolute that it contains within itself the ambivalence of simultaneously being a ‘no’. Yet even this negation is not, in itself, a question.

The true inquiry or questioning in his films is especially present in the adagi: Il taglio del bosco (1963), Incontro con il padre (1974), and Maria Zef (1981). In these moments, Cottafavi seems to be moved, but in hindsight he is not himself moving, but rather in a kind of phenomenological state that permeates the universe of his protagonists. This kind of depiction is exemplified by the repeated wanderings of his characters through the spaces — whose gravity is highlighted by the découpage — and also by the accent, in the construction of meaning, on the importance of the tool or utensil as an extension of these characters’ relationship to their condition of being in the world. Here, through longer sequences, there is an emphasis on the actions of the woodcutter or charcoal burner and their habits as a kind of organic extension of their bodies, inseparable from their individuality, in the case of Il taglio del bosco — or the gradual integration of Mariute with rural and domestic tasks in Maria Zef.

All of this unfolds through a shift from the centripetal gravitation based on more classical and Mourletian dramaturgical needs toward a rarefaction amplified by sobriety (his protagonists are men and women of few words), by a vernacular texture (the films are set in regions where dialect plays a prominent role, further complicating communication), and by a concentrated focus on sensation — on the moment, the passage, the elapsed time. Less classical — or perhaps closer to Ermanno Olmi or Valerio Zurlini, perhaps even to Luchino Visconti — Cottafavi nevertheless maintains, in general terms, a classical characterization. He does not depart from a more orthodox psychological portrait in which a character’s personality derives from the logical coherence of their behavior, preserving the maxim that ‘the more consistent the behavior, the more natural and plausible the impact’. [5] The key difference here lies more in corroboration through the addition of a certain pattern of conduct, rather than confirmation through symmetry and parallelism. There is an emphasis on this slow, gradual passage of becoming, which ratifies the character traits of his protagonists. There is conflict, but no contradiction; what is distinct is only the discovery and transfer to the foreground of self-knowledge and the journey.

V

Evidently, there are certain aspects within the cinematic spectrum for which the use of the musical metaphor is not sufficient. When it comes to narrative, it is diegesis that must attempt to reclaim its rightful role; however, the predominance of analyses of this kind in film criticism prevents it from being evaluated in direct relation to cinematic form. The result is narrative comparisons between types of characters or recurring situations in a director’s work, which fail to grasp how cinematic form breathes life into the skeleton of a script. In the case of directors such as Preminger, Fleischer, or Cottafavi — filmmakers who embrace diverse demands (whether commissions, freedom of thematic choice, genres, or distinct characters) — this leads to an inability to perceive the persistence of the same gaze moving across these assorted situations.

The gaze is itself a metaphor — not merely referring to how a filmmaker observes the visual aspects of their film, but covering an entire cosmology and the aesthetic principles that stem from it and bear upon the work of a lifetime. However, if we focus on the gaze in its strict sense, in its meaning in relation to the organ of vision, we can arrive at a different notion of the cinema of a filmmaker and, more specifically, of an author such as Cottafavi. This analysis should not disregard how this mechanism comes to life within the specific needs of cinema. In other words, if we are to talk about the gaze, we should not subordinate cinema to the visual arts, but observe how the image composition takes shape within the demands of each film.

Thus, it can be said not only that Cottafavi’s cinema is linear rather than pictorial in the way he organizes bodies within cinematic space, perceiving lines rather than masses, but also that, although there are chromatic affinities, particularly in his CinemaScope films, between his work and painters traditionally considered classical within art history (where primary colors — red, yellow, and blue — fall proportionally upon the organic spatiality of green or brown), his work resonates directly with Élie Faure’s remarks on Poussin, when he describes the unity of the latter’s art as ‘simply the result of an intellectual labor of conscious elimination, and of construction through the idea, wherein form and gesture, local tone, the general tonality, and the distribution of the volume and the arabesque respond to the central appeal of reason’. [6]

There is also a preference for flatness over depth, even though Cottafavi often mentions in interviews his use of diagonals (something noticeable especially in his CinemaScope films, where the format demands such spatial solutions, or even sporadically in Nel gorgo del peccato, in a shot involving Margherita, Alberto, and Filippo that would have earned the due praise of André Bazin, had he seen it, for its masterful handling of deep focus). But like certain masters who, anticipating the periods that would follow them, knew different techniques but preferred to abstain from them because they did not correspond to their aesthetic needs, CinemaScope becomes for Cottafavi a format suitable only for certain fables and stories close to man. If we wanted a film that took man as its focal point, it would be ‘necessary to adopt the Pythagorean proportions of the standard format’. [7]

If we were to regard Cottafavi’s cinema solely as a metaphor for visual aspects, we might initially believe that some of its features are closer to baroque art than to classical art — not merely because of the inescapable echoes of the timeless and domestic atmosphere of Vermeer’s paintings in Maria Zef, but also because there is a preference in this cinema for convergent unity over the plurality of the gaze distributed across multiple bodies. Or rather, there is an individual unity over a multiple unity. However, this pertains only to the framing of each shot when considered in isolation from its context, with the viewer’s gaze always gravitating toward its focal point and never drifting into distracting nuances. These shots, when placed within the flow of a sequence or the film as a whole, reveal an independence of the autonomous functions of their parts — a quality observable both in Il boia di Lilla and in La rivolta dei gladiatori. While not as strict as in Lang, this approach is nonetheless synthetic and sensualist, as in Matarazzo. And if they both converge, it is more due to the calculated proportions of certain colors within a whole, rather than a contrasting movement propagated ‘unchecked over paths and bridges from form to form’. [8]

In short, there may indeed be a need for individual convergence in making visual decisions, or even an occasional use of diagonal composition over flatness in certain shots throughout particular films. Yet, within its narrative function, this speaks more to a general articulation of forms than to any baroque dissimulation of these parts toward the convergence of a single prioritized element. The starting point here is, therefore, a centripetal form rather than a centrifugal one; obscurity is annulled in favor of clarity.

VI

In every art, the truly good man is the one who feels most deeply that nothing is given, that everything must be built, everything must be earned; and who trembles when he does not sense the presence of obstacles; and so he creates them... In him, form is a motivated decision

—Paul Valéry, Degas Danse Dessin

It must be noted, however, that Cottafavi’s body of work does not possess the kind of unity found in the work of certain filmmakers when it comes to formal decision-making and the certainty and reaffirmation of these decisions throughout their careers. One can identify not only an operative orthodox classicism across his oeuvre, but also four distinct phases, each carrying a specific methodological solution developed to address the particular problems they posed.

In the early part of Cottafavi’s career, the films are marked by a form of classicism that is not yet subjected to the more direct, codified, and systematic approach that characterizes his later period. It is a cinema where the rules are fully operative, although not as systematized into schemas. This balance between structural coherence and a certain permeability to the accidental is what defines films like Fiamme sul mare (1947, co-directed with Michal Waszynski), Fiamma che non si spegne, Una donna ha ucciso (1952), Il boia di Lilla, Traviata 53 (1953), Nel gorgo del peccato, Avanzi di galera (1954), and Una donna libera (1954). It is the period of rhythmic volatility, calligraphic linearity, and a spatiality more open to contingency, though already endowed with a strong internal logic capable of absorbing the unexpected.

In the second phase of his career, when he begins to work more specifically within certain genres, conventions are more systematic, and there is a tighter formal rigor in addressing the concrete problems posed by the material. Mastering the distinction between what is possible and what is indispensable, Cottafavi ultimately concludes that no contradiction exists between the two. This results in more universal forms and a reduced presence of the irregularities characteristic of more organic art — an approach that, precisely because of its rigor, offers viewers the possibility of following its every intricacy without exhausting its capacity to enchant. This is the period in which the mode shifts from questioning (and responding to questions) to direct affirmation. It includes La rivolta dei gladiatori, Le legioni di Cleopatra (1959), La vendetta di Ercole (1960), Messalina Venere imperatrice, and Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide. It is the era of the fable in CinemaScope: of carefully measured sequences, of greater organization and distribution of bodies within the frame (as well as chromatic adjustments and the harmonization of these within the compositional and plastic aspects of the image), of stereotypical characterization, of the progressive flattening of narrative ambiguity in favor of transparency and rationality, and of a kind of deliberate vulgarity achieved ambivalently through formal sophistication.

The third period is marked by transitions. It is therefore risky to treat it as having the same internal cohesion as the previous two, since new problems — the Brechtian influence, the shift from cinema to television — result in a nebulousness arising from the need to reconcile cosmological propositions, means of production and his own aesthetic heritage. The search for an internal order is not set aside, but Cottafavi seeks to absorb these other elements that may initially destabilize the system. I cento cavalieri is the meridian between the second and third phases, where the fabular tone begins to acquire a slight internal ambiguity: while closer to the second phase when reaffirming some of its narrative and formal components, it also intensifies, on the other hand, a sense of laxity and impurity that vigilantly dominates the very process of film craftsmanship. Although still fairy-like and realistic, the register becomes self-aware and — in due proportion — structural, generating a consciously impoverished cinema. In his television works — Sette piccole croci (1957), La trincea (1961), Operazione Vega (1962), Ai poeti non si spara (1965), La fantarca (1966), Il processo di Santa Teresa del bambino Gesù (1967), and Missione Wiesenthal (1967) — there is a pronounced ambivalence: an increasingly evident televisual narrative simplicity imbued with a strong and blatant allegorical clarity.

The final phase of his career is neoclassical. Le Troiane (1967), Antigone (1971), and I Persiani (1975) may, at first glance, seem more aligned with a Brechtian perspective — especially if one inadvertently associates Antigone with the work of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet. However, upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that here Cottafavi submits more to Greek tragedy than to epic theater. While there is a shedding of simplicity and clarity, there is likewise an increasingly dominant tendency to eliminate any remnants of emotivity and expressiveness in favor of greater objectivity and coldness. This mirrors Stravinsky’s preference for certain instrumental textures, avoiding strings as though seeking to escape sentimentality; Cottafavi retains in his sequences and shots the same unorthodox rhythmic interest that characterizes the Russian composer’s music.

This essay was previously published in Foco – Revista de Cinema, issues

8–9, and has been translated and adapted for Narrow Margin.

Notes

Éric Rohmer, Ensaio sobre a noção de profundidade na música: Mozart em Beethoven (Imago, 1997), p. 98.

Michel Mourlet, ‘On a Misunderstood Art’, trans. by Gila Walker, Critical Inquiry, 48:3 (Spring 2022), 483–498 (p. 493). Originally published as ‘Sur un art ignoré’, in Cahiers du cinéma, 98 (August 1959). pp. 23–37.

Rohmer, p. 127.

Ibid., p. 104.

Arnold Hauser, Mannerism: The Crisis of the Renaissance and the Origin of Modern Art, 2 vols (Routledge & Krgan Paul, 1965), I, p. 121.

Élie Faure, History of Art: Modern Art, trans. by Walter Pach (Harper & Brothers, 1924), p. 165.

Michel Mourlet and Paul Agde, ‘Entretien avec Vittorio Cottafavi’, Présence du cinéma, 9, December 1961, 5–28. (p. 16). An English translation is available here: https://theluckystarfilm.net/2025/03/12/translation-corner-vittorio-cottafavi-in-presence-du-cinema/.

Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History, trans. by M. D. Hottinger (Dover Publications, 1950), p. 161 (translation modified).