What happened, happened. Each one knows themself. We must try to be within what happens to us. Facts are never what they seem to others.

—Barbe Zef

When I was young, I read in a book that Alexander had pacified Persia. It was very beautiful to read that word, ‘pacify’... Some years later, I found out he had killed all the men, enslaved the women and deported everyone, and so it was pacified.

—Vittorio Cottafavi

Cottafavi had always been very concerned with freedom. Gradually, this freedom — thematic in the early melodramas, an object of the characters’ pursuits — led him to discover the freedom he himself owed to his characters and, by extension, to the spectator.

The final composition in the ‘scena madre’ of Una Donna Libera (1954): after Liana kills her former lover, the camera sits still by his enormous dead body while she remains out of focus in the background, before she drops the gun and leaves the scene like a ghost, almost unconsciously: is there a more just way to frame this moment? What begins as an alignment of the mise en scène with the protagonist — the sudden burst of violence in the character matched by a sudden cut to a close-up push-in of her firing the gun; after this rushed frenzy, the realization of her own actions and her dissociation matched by a cut to the focus of her attention (the dead man, though not from her point of view) while she herself is nothing but a blur — leads to a more objective assessment of the events: a psychological approximation with the character, but also the concrete consequences of her actions, both in the same shot. Later, the satisfaction and acquiescence we get from Liana’s final surrender to the police is born neither from moralism nor from a condescending presumption of her innocence: the focus is rather on how she accepts her own fate as an act of free will, conscious and uninfluenced by others or by bursts of emotion. There is a sublime irony in how the ‘free woman’ of the title finds her freedom in prison, which intr oduces a dissonant note among the perfect harmonization of all the elements of the mise en scène. [1] The character struggle against the fatalism of her condition as a woman in 1950s Italy is at the same time a struggle against the fatalism of melodrama (the film is very self-aware; near the end, the villain tells the heroine: ‘We’re in the midst of melodrama, at the climax!’). Paradoxically, she obtains her freedom precisely by accepting this fatalism, in an act of noble resignation (as Cottafavi resigned himself to work within a genre he despised? But let us remember that ‘The fact you choose your own prison’, as another filmmaker said, ‘gives you absolute freedom’ [2] ).

Una Donna Libera. The pianist and the killer.

Soon after making this film, Cottafavi would start working for RAI. [3] In his notes to his 1958 television adaptation of Antigone, Cottafavi shifts the emphasis of the play from the gods’ fatalistic determination of the tragic events to man’s individual agency: ‘Fate isn’t a fact external to man, imposed upon man; it grows within man himself, out of man himself, and determines events through man’s voluntary actions: thus man participates in divinity.’ [4]

After the box-office failure of his melodramas, another change in career, parallel to the TV work: the ever-growing canvases of the peplums and historical epics, in which Cottafavi deals with more characters, with whole societies, with political forces — be they those of the Greek council that sends Hercules on an expedition to a fascist Atlantis, or the palace intrigues of Messalina. These forces gradually render this ‘freedom’ less a manifestation of thematic intrigue or the characters’ ambitions — that is, something to be attained — and more an inherent condition of one’s actions, as responsibility and free will, as the trajectory of Liana in Una Donna Libera shows. It is a condition established by the filmmaker for his universe, contrary to the fatality of melodrama.

All of this, of course, is parallel to a growing interest in Brecht that first arose in the modest proportions of a cheap adventure film, Il Boia di Lilla (1952): ‘I inserted an ironic element in it, which was born out of my studies on Brecht. I aimed for estrangement, to the extent that it was obtainable’. Cottafavi’s mixed feelings for the genres he worked in naturally left him at a distance in regard to the material: ‘My attempts at this began as soon as I saw myself in front of the characters with their period costumes and swords: in them, I saw beauty and ridicule.’ [5]

Theorizing in ‘Brechtian Aesthetics and Television’, the director writes:

The estrangement, this tearing of the umbilical cord linking the actor to the character and the character to the public, has liberated the character from the sentimental mud against which he floundered in bourgeois theater, linked in a single embrace to his performer and his audience, and has left him detached, free and exemplary: one ‘different from us’ with whom we can argue, who can convince us, whom we can refute. [6]

This movement from the freedom for which the characters search to characters which are left ‘detached, free and exemplary’ as part of Cottafavi’s approach to material he found at least partially ‘ridiculous’ culminates in I Cento Cavalieri:

The narrative doesn’t follow a preordained, conceptual construction, but observes the facts as they happen, at the moment they happen. This is why contradictions appear; why there are not goodies and baddies, but only more or less bad men; why the story develops by chance instead of causality; and why the characters are partial, fragmentary and sometimes even contradictory. [7]

A new kind of narrative structure that not only favors chance, liberating its characters from melodramatic fatalism, but that in so doing also tries to liberate the spectator himself in regard to the film. The film is not centralized on a single protagonist; characters are instead posed against each other without a particular perspective being privileged, and spectatorial identification is not abolished, but dialecticized (as Cottafavi explains in ‘Brechtian Aesthetics and TV’, and as we can already incipiently observe in his camera’s exterior, critical view of Liana at the end of Una donna libera). It is openly Cottafavi’s most Brechtian film for the cinema; strangely enough, it is also Michel Mourlet’s (a notorious hater of Brecht and historical admirer of Cottafavi) favorite film by the Italian director:

[...] his masterpiece remains, without a doubt, 'I cento cavalieri', the last film he shot for the big screen. In it, we may find all the tendencies of his inspiration gathered in a truly Shakespearian symphonic composition: the tragic, the burlesque, the haughtiness in relation to the story, the sense of history, the mastery of pure action, the plastic experimentation, the cruelty, the poetry. [8]

This is not the first time Mourlet praises a Brechtian (Joseph Losey was not only influenced by, but also a collaborator and friend of Bertolt [9] ), and particularly a Brechtian who’s not usually discussed among the other more notable Brechtians of the cinema (Godard, Straub-Huillet, Glauber [10] , etc). Which is just another reason why we should take a deeper look at Cottafavi’s formal tactics in this film.

(An expansion of the Brechtian cinematic canon is necessary not only to include the likes of Cottafavi and Losey, and even Rossellini [11] , but also to enable a wider perception of Brechtian and political cinema in general, which would also include directors who perhaps weren’t even familiar with the German playwright, be it Chaplin, whom Brecht himself admired, or Ford, whom Straub called ‘the most Brechtian of all filmmakers’, [12] or even names such as John Carpenter, whose They Live bears lots of similarities to Brecht’s Galileo, [13] and perhaps even Jean-Claude Brisseau in his most pedagogic moments; directors who, while remaining faithful to a realist, dramaturgical, fictional cinema, pointed towards new possibilities for a political cinema, one that should strive to be ‘popular and responsible’ [14] and, therefore, modern. Brecht: ‘It has got to be entertaining, it has got to be instructive’. [15] And we’re not against Godard or S-H, lest we be accused of being reactionary!)

* * *

I Cento Cavalieri is both an epic film and a parody of an epic film, equally and simultaneously, one thing reinforcing the other, the comic and the ridiculous incessantly alternating with the tragic and the epic, with an impressive confidence in its tonal shifts (‘epi-picaresque’ is how the film is described by a self-aware Don Gonzalo in the film’s brilliant trailer, directed by Cottafavi himself). [16] For Cottafavi to obtain his demystification of History, mystification must exist in the first place: so there is the framing of the ‘epic film’, the heroic people (violent and ignorant) fighting for their freedom, their noble heroes (a ‘Don’ whose title is as quixotic as his helmet), a damsel in distress (stubborn, unafraid of men and of flaunting her sensuality), menacing villains (either hungry idiots led by a dwarf or the mighty Arabs, whose leader, however, is often shown as a fool). The topoi are there, and work as such, but each is also balanced by a counterweight.

The grandiosity of History reveals itself to us in its mundane, concrete truth, the pettiness of practicality, contingency, interest, power, violence, need, political machinations and instincts of self-preservation, in a game of action and reaction that is as rigorously causal as it is filled with errors and accidents.

‘Phenomenological’ is how Cottafavi describes his own film. [17] In this sense, we could compare it to an apparently very different work: Éric Rohmer’s L’arbre, le maire et la médiathèque (1993). Both are political films not insofar as they discuss political themes but in how they deal with the very field politics — or more specifically in Cottafavi’s case, History — plays on. Both films are infiltrated by things beyond the designs of their characters — Cottafavi’s films opens itself up to their stupidity, Rohmer’s to chance, and it is these elements that end up leading social events more than the particular will of any one person or group. In both films there is a decentralization of the drama, a necessary balance of different characters and groups to avoid any one of them obtaining primacy over the others, to ensure that all of them are constantly situated in relation to one another, with their different worldviews described and opposed against each other, one thing contradicted by the next. This allows for a revelation of the limitations of the characters, of the groups, and of their discourses as they confront a reality that goes beyond themselves. There is what one says, what one believes, what one wishes for, what one expects; and then there is what is actually true and what actually happens. Both films bring their haughty subjects and ideas, History and politics, down to the ground floor.

* * *

Less than twenty minutes before the end of I cento cavalieri, there is a key three-shot sequence during the crescendo towards the climax: Don Fernando, together with the group of bandits led by the angry dwarf, follows a suggestion by the cunning friar (who, alongside the Sheikh’s son, might just be the only character in the film to demonstrate some intelligence — always framed as a pragmatic, down to earth intelligence, contrary to what his profession might suggest) to set the wheat fields ablaze. It’s a scorched-earth tactic to deny the Arabs the resources they’re after in an attempt to repel them. From shots of our presumed heroes running aimlessly with torches in their hands amidst the fire, we cut to the friars shut in the monastery, holding candles and marching ceremoniously. One of them asks, ‘Sorry brother, but don’t you smell something burning?’, to which the other responds, ‘And a great fire shall come from the sky, and will scorch the earth, and Christ shall rise in all His Glory!’ (it has previously been established that they are awaiting an imminent Apocalypse). He raises his arms in praise, and then we cut to the sentinel of the Christians’ camp who, unaware of Don Fernando’s plans — the lack of communication is a testament to the rebels’ incompetence — screams, also with his arms raised and equally oblivious to what’s actually happening, namely that ‘The Arabs are burning the fields!’.

3-shot sequence from I Cento Cavalieri (the second shot in the sequence, a semicircular pan, is represented by two stills).

The scene with the friars (a single shot) is inserted into the film’s continuity with a function of commentary: these characters aren’t directly involved with these events at this particular time, nor will they be relevant later. Through the repetition of elements that come before (the candles that rhyme with the torches) and after (the raised arms, the speculation as to what’s happening), the scene operates a creative transition between two moments. It’s a comparative analysis: although the sudden cut and the drastic differences in tempo and volume between the shot of the friars and those that bookend it establish a clear contrast, there are recurring elements that draw an equivalence between all the characters involved. Opposing statements are made, but both are shown to be equally wrong. The film does not privilege any particular point of view, instead allowing the spectator, who knows the truth, to observe them objectively. Moreover, a deeper idea is articulated: through the montage’s opposition between the friars — with their white robes, ‘neutral’ in relation to the blue/red scheme that distinguishes Arabs and peasants; the fact that they inhabit an enclosed, dark space, separated from the rest of the world, allowing them a sort of artificial peace and tranquility dislocated from the conflict taking place; their calculated, ceremonial gestures; the abstract, rhetorical statement of the friar responding to the other’s question with a non-sequitur — and the running peasants and screaming sentinel, who respectively act on and react to the visible world, out in the open, hysterical, nervous and confused, Cottafavi cinematographically inscribes a phrase by Brecht: ‘[...] but mankind’s highest decisions are in fact fought out on earth, not in the heavens; in the “external” world, not inside people’s heads.’ [18]

But this inscription is colored by an obvious touch of ridicule: the fact that it’s a question of mankind’s ‘highest’ decisions does not imply that those responsible for those decisions, willingly or not, are the highest among us.

The idea of divine intervention, vertical and hierarchical, proposed by the monk, as well as any explanation that could exist in full in a single shot or from the mouth of a single character, is opposed by sequentially contradictory facts of equal importance (that is, equal falsehood), favoring the film’s ‘horizontal’ articulation through a properly intellectual montage: it is the clash of ideas, and not dramatic progression, that propels the cuts. The setting is the year 1000, but the film shows it to us with modern, secular eyes.

Contradiction effects by montage are abundant throughout the picture and this mechanism is one of the work’s main formal tactics. Brecht’s formula for the actor ‘fixing the “not..., but…”’ is transposed to the narrative structure:

When he appears on the stage, besides what he actually is doing he will at all essential points discover, specify, imply what he is not doing; that is to say he will act in such a way that the alternative emerges as clearly as possible, that his acting allows the other possibilities to be inferred and only represents one out of the possible variants. Whatever he doesn’t do must be contained and conserved in what he does. In this way every sentence and every gesture signifies a decision; the character remains under observation and is tested. [19]

Frequently, as in this scene, such effects first fulfil a comical function: an expectation is subverted. Greater meanings arise by the gradual accumulation of this procedure: the film consistently demonstrates how what the characters think, say or do is foolish, inconsistent with reality, or an outright lie, revealing their true interests. That which they believe or desire is often immediately tainted or revealed as false. Factual reality unmasks discourses, speculations, interests, and it is through this mechanism that the film most often operates its scene transitions. There is a continuous interplay between all parts of the film, with all sorts of more or less complex variations on this effect — for example, when Don Jaime invents the story about the Sheik in an attempt to convince the skeptical Don Fernando to pay more for the grain, the unexpected appearance of the Arab messenger supports Jaime’s fiction and contradicts Fernando only superficially; aware of the scene’s subtext, we realize that the truth is actually the opposite. Our perspective is not aligned to any particular character’s point of view; they’re both wrong.

Very simply, someone says something, and the film shows us the opposite is true, or vice versa: it wasn’t God burning the fields, nor the Arabs. Is it perhaps this ability of the camera to reveal the visible world against the characters’ rhetoric that preserved the film’s fascination for Mourlet?

* * *

This ‘not..., but…’ montage technique is used since the first cut in the film, which arrives at the end of its opening scene, consisting of a single four-minute-long shot that requires careful consideration.

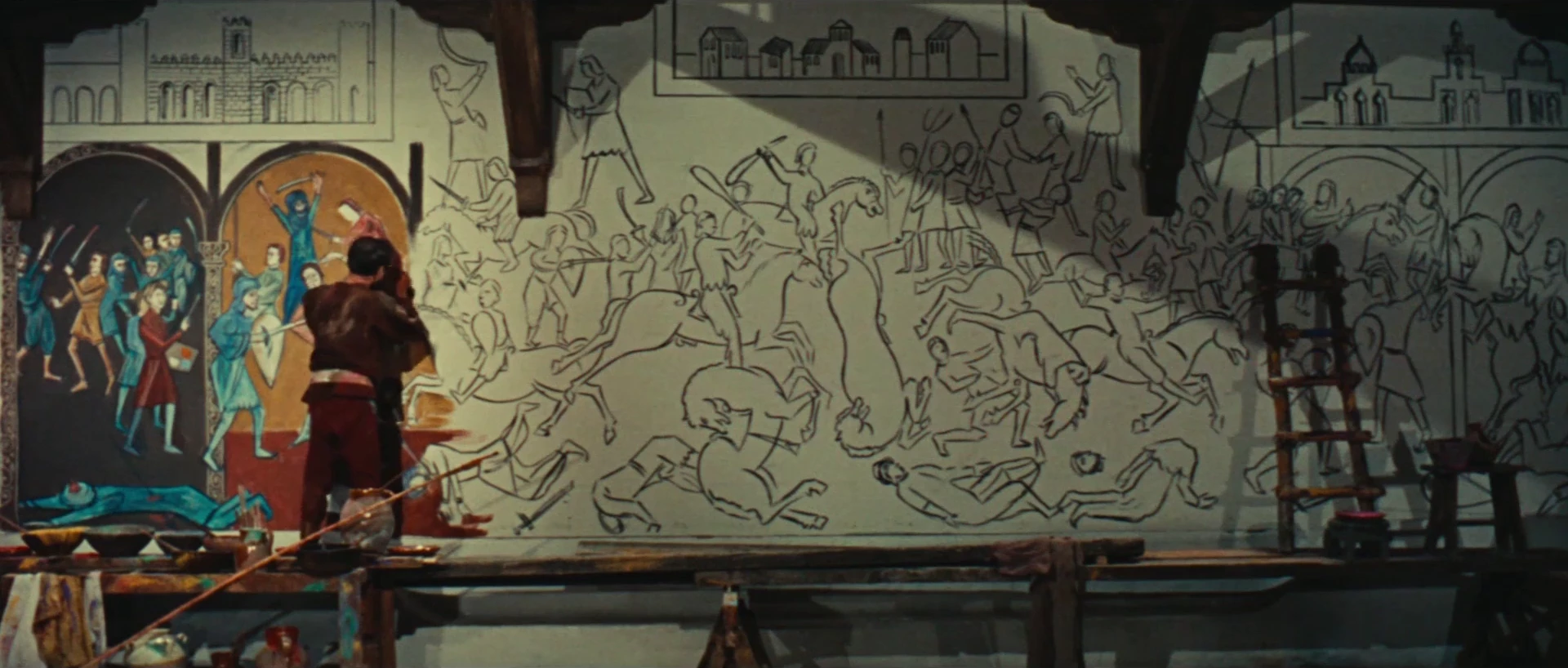

During the opening credits, we see a painter working on a fresco. He is short and splattered with paint, scratching his back with his brush and doing all sorts of strange poses; seen from behind and at a distance, his body language suffices to describe a ridiculous sort of figure. He then turns and approaches the camera, takes a look at a bucket of paint and, talking to himself, opens the film with the question: ‘This red and this green are the same. But how to tell red from green?’

Which is absurd. Can’t he see? Could a painter be color-blind? What does he even mean? Something deeper, perhaps: how to interpret reality, how to distinguish things, even the simplest ones, one from the other? Is there a significant difference between two things, despite their apparent contrast? (This is precisely what is at stake in the cut from the friar to the peasant sentinel discussed above; like Intolerance, we could nickname I Cento Cavalieri ‘a drama of comparisons’.)

The painter soon notices the spectator looking at the fresco, stares directly into the camera and starts screaming, telling us to leave the place. We’re in a forbidden room, he says. What is it that we’re not allowed to see and, more importantly, why are we not allowed to see it?

First shot of the film: The painter and the fresco.

On the wall, we see his fresco, still far from finished: it depicts a battle scene. In the portion that has been colored, there are Arabs dressed in bright blue — celestial, noble and artificial — fighting the Christians in their reddish-brown robes — more earthy hues. In the rest, only the contours of the figures in black and white. We’re in a sort of historiographical antechamber, which bookends the film: History still as a series of indistinct figures, facts yet to be interpreted, whose particular colors shall be added in a later stage — and, apparently, somewhat arbitrarily by a very unreliable color-blind painter.

The film’s trajectory, as we’ll see, is the opposite of that of the painter. Simultaneous to the fabulous idiosyncratic richness of characters and situations throughout the film, there is a ‘leveling’ of them all (it’s hard even to say if there is a protagonist in the film, such is Don Fernando ridiculed), a dehierarchization, a demystification which will ultimate lead to the climax’s desaturation.

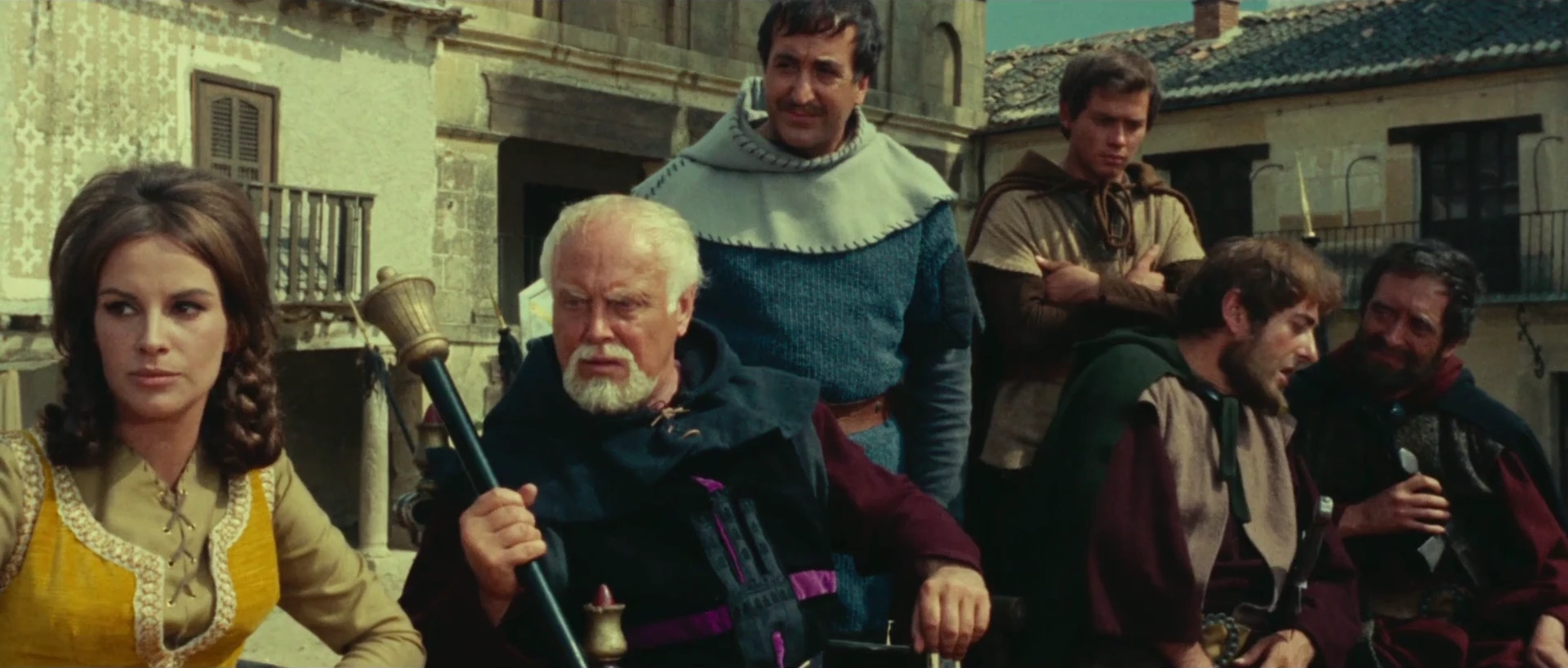

The ridiculing of the painter, his initially oppositional stance, and his direct addresses to the spectator are crucial to the film: we are put at a distance from his point of view and his opinions; we mistrust him. Soon his untrustworthiness and self-interest are made clearer to us: he admits to embellishing himself in the fresco, and remarks on the cleverness of his fellow countrymen in dodging both Arabs and Christians: ‘And so we didn’t pay taxes to either one or the other! We were a calm, peaceful people…’, and the film cuts to the past, to the actual beginning of the story, with a crane shot diving into a crowd of the so-called ‘peaceful’ peasants beating each other like crazy in the middle of a street (Not..., but...).

Second shot in the film: Peaceful peasants.

We could compare this framing device to those which bookend other films by Cottafavi, particularly his melodramas (Il Boia di Lilla, Una Donna Libera, Nel gorgo del peccato (1954)...): previously, such a device introduced the female protagonist, portended tragic events, provoked some sort of anguished expectation, involved us in the drama through a retrospective flashback, a subjective psychological dive, etc. Here, the same device has very different effects: it arouses suspicion, raises questions, confuses and directly provokes us, breaking the fourth wall while at the same time separating us from the narrator, making us question his version of the facts.

* * *

If the film’s opening scene was a sequence shot, the second one already introduces new spatial-stylistic devices. Wide shots of a street filled with a tumultuous crowd are contrasted with shots of a merchant who tries to appease them, screaming from a balcony above. The découpage, like the montage, works in accordance with the narrative structure, facilitating alternations between different narrative threads — a shot following the previous one in the same way that a scene is opposed by what follows it. The merchant is never shown in relation to the protesters in the same shot, the scene being organized in a more constructive découpage. This technique is repeated twice more in the same location, like a musical motif, the porch itself coming to signal relative power: first, a few scenes later, it is Don Jaime — the silly nobleman who’s to marry Sancha, the Alcalde’s daughter and the film’s heroine — who is on the porch trying to appease the peasants, until an egg is thrown on his face: the egg’s virtual trajectory in the edit is the only thing that connects the peasants and the nobleman in a shot/reverse-shot.

Take that, synthetic construction of space!

Then, a little later, just as Don Fernando is about to leave town with his grain and after he belittles Sancha to his companions — ‘no matter how hot-blooded she is, I don’t care to even look at her face’ — he suddenly sees her face staring at him from above with a smirk (Not..., but...). The opposition of shots, linked by a cut that matches their eyelines, is simultaneously a gag and a tender preview of their passion, marked by their stubbornness and opposition to one another (in their previous scene together, Sancha had exited while Fernando stood and stared at her from behind: the woman is always above and one step ahead of the man — that is, until Fernando sacrifices himself to be tortured near the end of the film, sealing their bond). This articulation of space in separate, starkly different fields of view that cohere only through the edit introduces each character, or group of characters, as a separate agent in the story, with their own interests and relative power to one another.

Don Fernando, standing in front of the pit where he will eventually be tortured: ‘I don’t care to even look at her face…’

Her face.

These first minutes of film are stunningly quick. In a very short space of time, and with great fluency, the film shows us Don Fernando’s attempts at buying wheat, the striking peasants attempted negotiation at the Alcalde’s palace, and the arrival of the Arabs. A very rich and interwoven set of characters and social groups are introduced, in opposing pairs: the crowds and the merchant, Don Fernando and Sancha, ‘union leaders’ and politicians, and, ultimately, Arabs and Christians, the Arabs thus unifying all the others, equalizing them as mere superstitious fools in opposition to the Arabs’ own rationality. On a basic level the story follows the traditional mold of a group of characters who need to come together to fight a common, foreign enemy. In the scene where the Arab messenger first arrives, Cottafavi’s style is initially very theatrical — a very long take of the discussion between serfs and lords, with the camera at eye level around the table, as if we were there during the negotiations. All the characters are shown simultaneously, arranged in depth. There’s a striking moment, however, where several characters point and look at some unseen figure just beside the camera. It seems almost as if they were breaking the fourth wall, inviting us into the discussion table, almost soliciting us to defend ourselves and weigh out the arguments that make up the discussion.

Still from the long shot that opens the scene.

Then the scene alternates between the peasants outside, Don Jaime at the balcony (the egg scene), then back inside, in a very fragmented manner (the curious thing is that Cottafavi manages to be fragmentary while using only very wide shots; this may very well be a consequence alternating between completely different sets and locations while constructing this sequence of a room with a balcony overlooking a street). When the Arab messenger arrives, he too is shown in a shot spatially separate from all the Spaniards, who are shown together.

A cut to the Arab leader standing alone, then back to all the Spaniards together.

As the scene progresses, there is another stark cut to Sancha and Don Fernando, who had almost disappeared in the background, now staring through a window, before we see, through their point of view, the Arabs arriving at the city, each thing very neatly separated from the other, with no contiguous spatial continuity between shots.

Three consecutive shots with no spatial contiguity.

The cut from the Arab messenger to Sancha and Fernando by the window almost feels like an ellipsis, even though it isn’t. Their movement towards the window is barely visible in the previous wide shot of the Alcalde and Don Jaime talking to the messenger, so there’s some trouble in apprehending the spatial continuity of their movement. And anyway, their movement towards the window is completely arbitrary, and the couple of shots of them and of what they see serve merely as a commentary for the attitude of the Arab messenger: ‘Now I understand why everyone is so silent’, Fernando says, euphemistically, as he sees multiple Arabs who’ve taken over the town square. Those couple of shots are an intrusion, an interruption; that which Sansha and Fernando sees changes our perception of things, so that, at the end of the scene, when we finally see all the characters together and understand their relative positions, the Arab messenger, who we’d just seen smiling in a close-up, is now seen impersonally from behind, his relative size and his battle shield plastically, aggressively dominating the shot (it’s the only over-the-shoulder shot in the sequence; the over-the-shoulder, of course, being a composition able to operate a change in field of view that maintains the relative positions of characters explicit within a single image). Fernando and Sancha’s silhouettes are almost unnoticeable in the background, by the window, strangely motionless; their presence is not felt in the shot, and the opposition is constructed entirely through the edit, whose articulations are made possible by, and in turn inform, the changes in framing.

Final shot in the scene.

In other scenes, the way the bandits are introduced is also very fragmentary: initially, a couple of brief single-shots of a crippled beggar intrude in between wide shots that would otherwise proceed for long durations (more than a minute each). These interruptions arise seemingly out of nowhere, with no explanation as to what the new character is doing there, presented as he is in tight shots with no contiguous spatial relation to the rest of the scene. Initially it just seems like a comic addition, the beggar counting the grain spilled by the merchants; only scenes later will he toss his cripple-cart and reveal himself to be one of the criminals in disguise, spying on the grain merchants. His intrusions in the first few scenes of the film sets off a musical motif (over the shots of him, in the score we hear the melody the bandits will sing as they entrap and rob Don Fernando), while the bandit’s repeated intrusions themselves, like a staccato note, are a visual motif present in these first few sequences.

A couple of intrusions by the fake-cripple bandit, out of nowhere, in two different scenes. He’s seen completely separately from all the other characters in the scene, in an insert all his own.

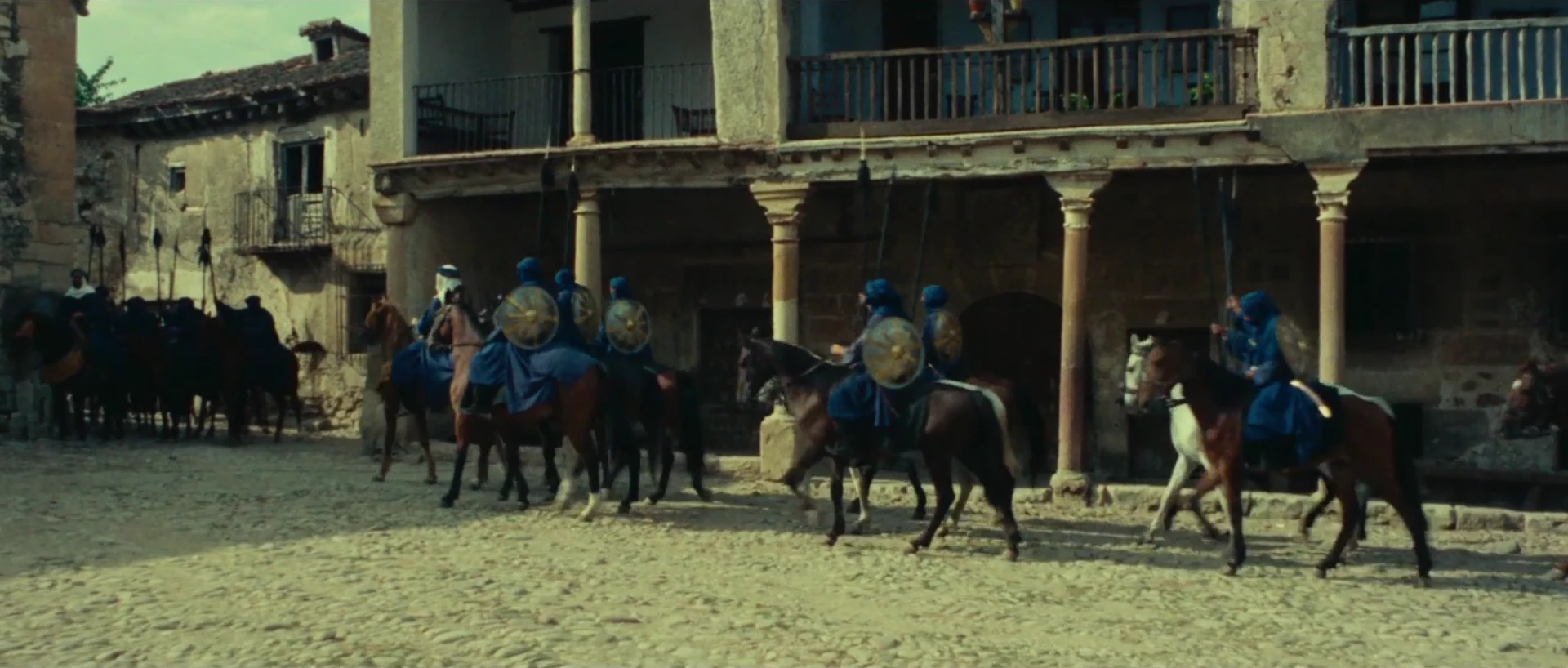

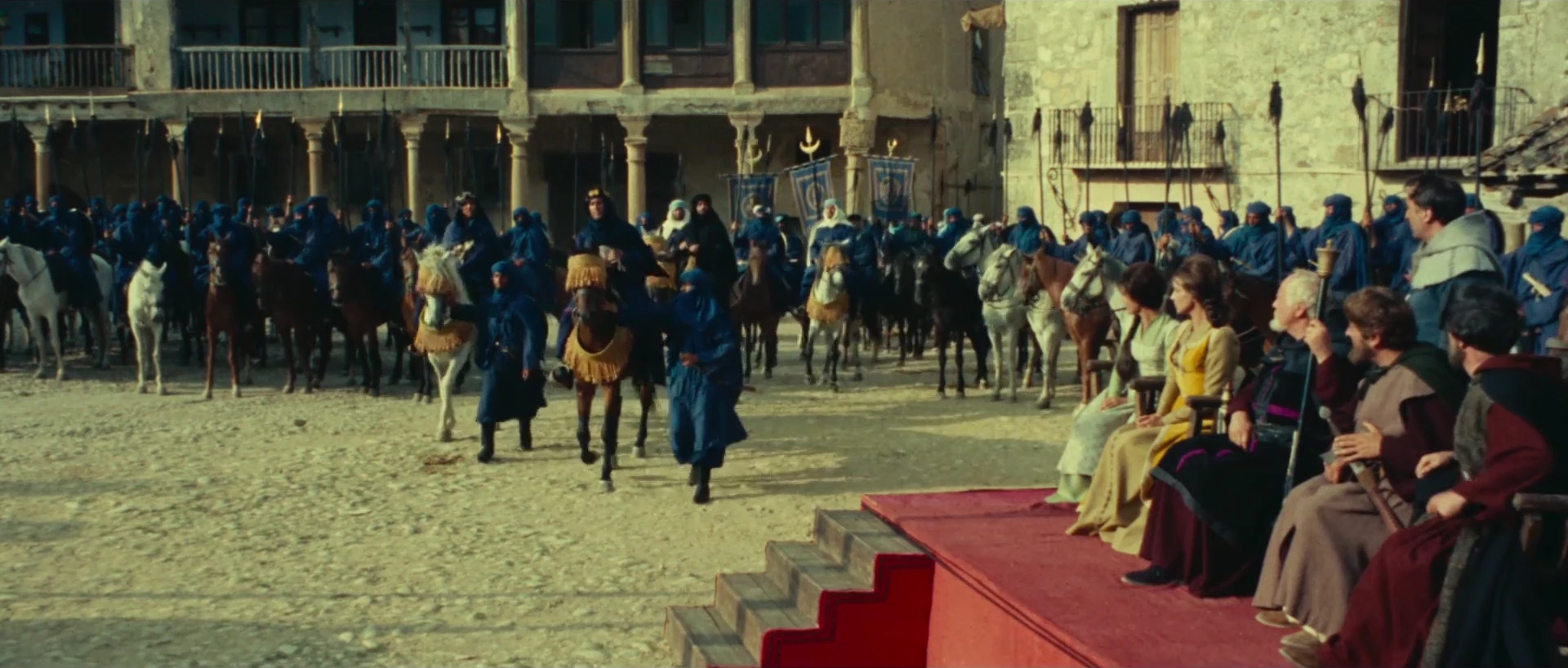

But the most fragmented sequence in this first act of the film, which reminds us of the Bachian inspiration Cottafavi confessed to in regard to the climax of his earlier film Fiamma che non si spegne (1949), [20] comes when the Arab cavalry arrives in town. First, a wide shot with a wide-angle lens, at a skewed angle, of the Alcalde’s entourage awaiting the Arabs — a very classical composition with a light accentuation of the depth of field. ‘Not..., but…’: after the Alcalde has raised concerns about hosting all the Arabs in the town, and one of his advisors has responded, ‘No more than a dozen Arabs, there won’t be any problems; listen to how quiet it is!’, the film immediately cuts to a whole battalion entering the square, as if they were already there, lurking; their appearance after the advisor’s comments is a very unrealistic jolt. There follows a series of descriptive panning shots from right to left, connected by the musical score, of different squadrons entering the square in succession, each from a different corner. As one by one they merge together — first led by one, then two, then three Arab commanders dressed in white — their simple numerical progression is almost lost between the ellipses, the musical and plastic emphasis, and the repetitiousness of the scene. The next battalion always shows up in the very corner of the TechniScope frame and the cut always comes when we’ve barely had time to notice it, creating the quasi-magical impression of an infinite series of Arabs entering through an infinite number of corners. Even when the screen is almost completely filled with Arabs, and these forcibly stop their advance as they reach a wall, the film cuts to a different angle and, inexplicably, they just keep coming. Once this musical interlude is over, it cuts back to the Spaniards and, out of nowhere, with no previous continuity, as if the film suddenly returned to its narrative interests, there appears, for the first time, Abengalbon, already in frame, approaching our heroes standing on a small red-draped island surrounded by an ocean of blue uniforms. The entrance of the Arab leader has thus been abstracted as the entrance of his whole army, the character representing more than just himself.

'No more than a dozen Arabs, there won’t be any problems; listen to how quiet it is!'

First of a series of shots of Arab troops entering the square. No more spatial reference to the Spaniards. As soon as the other Arab captain (wearing a white hood) appears at the left side of the frame, it cuts to the next shot.

Almost identical to the previous shot, but now with two Arab captains leading the troops. The architecture of the buildings around the square is too similar. The repetition creates a disorientation, a loss of scale and of numbers.

It seems the troops have stopped, facing a wall...

But, inexplicably, through a shot change, they just keep coming.

Back to the Spaniards. Out of nowhere, there appears Abengalbon.

The very particular mix of wide, theatrically staged long takes with very fragmentary montage in these early scenes — the brief intrusions of extraneous shots, the rapid alternation between different spaces and characters, the dramatic swings between synthetic and constructive treatment of space that always avoid analytical découpage — aims to set the stage of all that is to come, establishing all the different social groups and the network of financial, political and emotional interests that motivate them. Always, one thing is put in relation to another, space is constructed through a host of oppositions, fractures and commentaries are inserted during or immediately after scenes.

* * *

The most assertive use of this separation of spaces comes in the anticipation for the final battle. First, a montage sequence alternating between the Arabs’ and Christians’ preparations; the Arabs silently, orderly, marching towards their horses, taking up their weapons; the Christians chaotically climbing the animals, Don Fernando hurriedly dressing himself, women and friars running around. The armies are finally ready, opposing each other in an open field. The Arabs, seen in incredibly fast lateral tracking shots, start riding towards their enemies first, who remain standing still, preparing their spears; the alternation between movement and stillness is somewhat comical but also creates urgency for our heroes. There’s no shot that features both armies; once again it’s all constructed in the montage — so even as the Christians begin to charge, we have no idea how far both armies are from each other, and the precise instant of the inevitable clash remains a surprise (although the aimed effect is much more discreet, it’s essentially not unlike the famous scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail of John Cleese’s surprise charge against the castle).

The Arabs charge against the Christians, still getting their weapons ready.

After this series of opposing tracking shots, which very neatly respects the 180 degree rule — Arabs advancing from screen-left towards the right, Christians from screen-right towards the left, the first clearly identifiable in blue and the second in red — at the moment when the two armies finally clash, the filmmaker suddenly turns the whole image black and white, just like the unpainted fresco, and the geography of the battle becomes an absolute chaos of jump cuts, extreme close-ups and quick pans. All characters become indistinct from each other, while the epic score turns into a frenetic clapping of castanets. Suddenly the battle that the film was building towards, and which we may assume was the central expectation of the spectator of such a big-budget spectacle in the 60s, loses all its grandiosity. The elegant mise en scène of wide shots, the clear spatial separations which established motivations, all this is blown up along with the colors themselves, as all motivation and all separation loses sense amidst the violence. No heroic feats, no moments of heroism; a fight to the death with the most rudimentary resources. Just compare it to the duel between Don Fernando and Prince Alaf a couple of scenes before; there’s no swordsmanship, no honor, but rather horses toppling over, people jumping on top of another, scratching and kicking each other’s faces, strangling each other. It’s unlike any other battle scene in the cinema; the Sheik, the film’s main antagonist, is unceremoniously stabbed to death by the dwarf without even noticing what hit him; then, as the dust is settling, Don Gonzalo, our presumed hero, is mortally wounded. His son approaches and helps him stand up, consoling him.

In the most outright Brechtian manner possible, the character seems to observe himself from the outside as he’s about to die: ‘Am I wounded? Yes, I’m wounded…’. Then he is twice contradicted: he states, ‘Man is made for combat’ among a sea of corpses and, under the scorching sun, ‘it’s dark here’, with which his son, pitifully, agrees. Finally, before his last breath, he dissociates once again, as if narrating the events from the outside: ‘But... am I dying? I’m dying! I die!’

There are thousands of ways of filming a death. We could imagine a close up of Don Gonzalo, perhaps also one of his son; an image of his eyes and then of the sky literally darkening as they close; an approximation, an invitation into his personal suffering…

Instead we remain in the single wide shot, and the camera tilts down as Gonzalo drops dead and lays in identical fashion to an anonymous Arab soldier fallen by his side, their left arms stretched out. His death is rendered no longer singular, but merely one among many, friends and foes no longer differentiable.

Two mundane deaths.

And so, through the desaturation, the chaos of the edit, and the features of his mise en scène, Cottafavi filmically establishes the equality of men.

As color returns, we see Arabs and Christians once again united, harvesting grain together. The enemy, who had been shown in such stark opposition to the villagers, have now become just ‘another one of them’, in what we could see as a step in a possibly perpetual series of invasions, conflicts and unifications of all sorts of different groups throughout all of History (it’s obvious by now the film isn’t interested in the Middle Ages as much as in the twentieth century, and not so much in the twentieth century as in the idea of History itself). An impersonal third-person narrator, conspicuously absent from the film until this point, states:

[...] On the land bathed by the blood of heroes, the first grains have sprouted, which Arabs and Christians harvest like a gift. A gift that is the symbol of the happiness for which the Hundred Horsemen have fought, sacrificing their lives.

The introduction of this objective, ‘voice of God’ type narrator at the end of the film, and not at the beginning, is strange. Who are these Hundred Horsemen that now seem to be part of this village’s past, as he tells it? No more than the fabrication of one of the petty bandits in an early scene in the film, as he desperately tried to please the faqih while being whipped into a forced confession. His mundane despair has been sublimated into myth, passing as history.

The film’s coda cuts back to the painter’s room, where we see the fresco now fully painted, Arabs in blue, Christians in red.

And so History has been written, its color put into place, one way or another; facts otherwise random or false, characters once indistinct black and white figures lost in the confusion of battle, become legendary and grandiose representatives of their people. From the chaos of reality, from all the fragmentations and oppositions the film rendered into its form, an order is established by interpretation. But this order is arbitrary; the film has shown us it can and should be questioned. ‘This red and this green are the same. But how to tell red from green?’

And so we realize that it is only through this fragmented construction, through this constant alternation of viewpoints, the independence and interplay of its sequences, this constant ‘Not this, but that’, these constant confusions, misunderstandings and stupidities, that Cottafavi can show us these people as what was apparent from the very beginning — a collection of indistinct black and white figures, equalized in size by the flat perspective of a medieval painting and in their character by their lack of color, none the center and yet all integral parts of the fresco of History, irrelevant and decisive, free and submitted to outside forces, independent and interconnected, stupid and great, all part of the same eternal human comedy. And despite all the death and suffering, they will go on, sowing the fields together in an image of eternity. ‘Mockery is one of the elements of love’, says Cottafavi. [21] And maybe this explains why this most ridiculous of films is also one of the most joyous, and why, after all the death and violence, it ends in a marriage. For the film’s mockery of all is perhaps the hope that we may one day love ourselves as equals and live in peace. And be ‘as happy as it is possible in this world’, as the painter says in the end. Hopefully more than ‘a little’.

* * *

That was plenty of description of Cottafavi’s film, and we’ve barely scratched the surface of the incredible variety of its stylistic procedures, which play out as if innocent of any preconceived rules or restrictions. There would be a lot more to talk about; the range of different genres and registers, be it the epic, the melodrama, the screwball, sometimes an almost documentary-Rossellinian realism when we observe a scene from afar with a zoom lens that gives us the impression of watching a live broadcast from the year 1000 (the ambush of the thieves, or the Christian camp afire); the reinvention of Sergio Leone’s style in a sequence of extreme close-ups and zooms metronomically edited (when Sancha undresses and than covers herself to Don Fernando), the nonchalance and matter-of-factness of some of the briefest moments which somehow result in extreme pathos (the off-screen death of the friar, and Don Gonzalo’s salute to his corpse); the very modern use of jump cuts or aggressive angle changes (the series of push-ins in Don Gonzalo as he delivers his speech against a wall of crosses, the match-cut from the battlefield to the field being harvested at the end), the jarring inserts that seem to serve no narrative function but only a musical, rhythmical one (the whip-pan of the dwarf in a roof observing the torture of a peasant) — all this culminates in an unclassifiable film into which Cottafavi seemed to put everything he had ever done in melodrama, adventure, comedy, pepla, as well as everything he was doing and would go on to do on his TV works, the theatricality, the liturgy, the Shakespearian recitation, the distanciation effects. There is already in germ, in I Cento Cavalieri, some of the most striking elements of the didactic Vita di Dante (1965), where we see an even more preponderant use of the zoom, a similarly chaotic battle scene, memorable architectonic raptures (in I Cento Cavalieri, the sequence where the castle of the Count of Castille is introduced in a series of vertiginous camera movements that seemingly ignore the human figures, and the description of Dante’s Florence, when the camera snakes with an extreme concreteness and modernity through empty contemporary settings in the middle of a costume drama, and which curiously were already present in Cottafavi’s earlier, more modest melodramas — the descriptive pan of the empty living room in Liana’s house after her mother’s death in Una Donna Libera, the presence of the mother in Liana’s voiceover in contrast to her physical, concrete absence — and which can be found even in some travellings of a later chamber drama such as Il processo di Santa Teresa del Bambino Gesù, in sum, an ongoing spatial research by the filmmaker), a fragmented narrative with several different nuclei, etc. If these elements will lose some of I Cento Cavalieri's comedy, passion and joy in Cottafavi’s later TV works — colder, more abstract, more geometrical and distanced — they are nevertheless the distillation of formal experiments the director had been working on since his earliest films. The very self-awareness of I Cento Cavalieri, its winks to the spectator and fourth-wall breaks and framing devices, in germ already in Una donna libera, will transform into the director’s literal presence when presenting his Greek tragedies to the spectators of RAI — standing eye-to-eye with the public. We couldn’t imagine a more clear way of respecting the spectator’s freedom. After all, he, like us, like the monk or the Sheik or the dwarf, is just another character in this big fresco of cinema and life.

Cottafavi presents his 1971 Antigone to the spectators of RAI.

Notes

‘[Cottafavi’s] notion of mise en scène as the true transposition into cinema of a harmonic notion per se, with the subordination of the horizontal arrangement of elements (and therefore of the various ‘voices’) that make up a filmic work — sound, décor, montage, screenplay, cinematography — to the verticalized combination and conjunction of motivic needs and their subsequent development.’ Fábio Visnadi, ‘O Classicismo de Vittorio Cottafavi’, FOCO — Revista de Cinema, 8–9, 2016–2021. English translation published in this issue of Narrow Margin.

Eduardo Coutinho, interviewed by Carlos Nader in the documentary Eduardo Coutinho, sete de outubro (2013).

Cottafavi’s first work for TV was Sette piccole croci, in 1957.

Cottafavi, ‘Antigone,’ Ai poeti non si spara: Vittorio Cottafavi tra cinema e televisione (Edizione Cineteca di Bologna, 2010). Originally published in French as ‘Notes pour la mise en scène d’Antigone de Sophocle’ in Présence du cinéma, 9, December 1962, pp. 33–40. Subsequently published in Italian as ‘Antigone’ in Televisione, 1, April 1964.

Quoted in Gianni Rondolino, Vittorio Cottafavi: Cinema e televisione (Cappelli, 1980), p. 55.

‘L’estetica brechtiana e la TV’, in Ai poeti non si spara: Vittorio Cottafavi tra cinema e televisione (Edizione Cineteca di Bologna, 2010). Originally published in Televisione, 1, April 1964. English translation published in this issue of Narrow Margin.

‘Vittorio Cottafavi parle des « Cent Cavaliers »’, Cahiers du cinéma, 207, December 1962, pp. 775–77. English translation published in this issue of Narrow Margin.

Michel Mourlet, ‘Vittorio Cottafavi, Life and death of a great filmmaker’. Translation published in this issue of Narrow Margin. Originally in: L’Écran Éblouissant – Voyages en Cinéphilie, 1958-2010 (Presses Universitaires de France, 2011), pp. 189–191. English translation published in this issue of Narrow Margin.

In a note from March 1960, Mourlet called Losey ‘the cosmical filmmaker’ — see ‘Journal critique — extraits. Sur Joseph Losey’, in Survivant de l’âge d’or — Textes et entretiens sur le cinéma (Éditions de Paris-Max Chaleil, 2021), p. 83. Before directing his first feature, Losey directed the first US stagings of Brecht’s Life of Galileo, in partnership with Brecht himself and with Charles Laughton in the title role, in Los Angeles and New York in 1947. He also adapted the play into a film in 1975.

On a side note, Deus e o diabo na terra do sol could make a great double bill with I cento cavalieri; both were released in the same year, play on established genres, are set in desertic landscapes, and are guided by a similar humanistic idea of the liberation of man. Our analysis of Cottafavi’s film will echo that of Ismail Xavier in regard to Deus e o diabo: ‘In its functional aspect, the film’s modulation creates gaps through which the narrator can intervene in different forms. In its discontinuity, it opens space for explicit comments on its own imaginary. We thus have a representation that stretches out time, interrupts the action in order to comment on it, and freezes certain gestures to underline their social significance, as in Brecht.’ Sertão Mar: Glauber Rocha e a estética da fome (Cosac Naify, 2007), pp. 100–101.

‘In this particular crisis [of culture], cinema could truly take on an important role in offering a positive solution of its own; it could try to become even an irreplaceable medium, didactic, shall we say, also in the Brechtian sense.’ Roberto Rossellini, ‘Conversazione sulla cultura e sul cinema’, Filmcritica, 131, March 1963.

‘Andi Engel talks to Jean-Marie Straub, and Danièle Huillet is there too’, Enthusiasm, 1, December 1975, p. 12. The famous assertion, attributed to Straub, that Ford is ‘more Brechtian than Brecht’ is probably an apocryphal misquotation by Tag Gallagher.

The famous scene where John Nada tries to convince Frank to put on the glasses plays out analogously to that of Galileo trying to convince Prince Cosimo de’ Medici to look through his telescope in The Life of Galileo, Act 1, Scene 4.

Jean-André Fieschi, ‘P.-S. à Cannes: Les cent cavaliers’, Cahiers du cinéma, 180, July 1966, pp. 11–12. English translation published in this issue of Narrow Margin.

Bertolt Brecht, ‘The Street Scene: A Basic Model for an Epic Theatre’, in Brecht on Theater, ed. and trans. by John Willett (Eyre Methuen, 1978), pp. 121–29. Quoted by Cottafavi in ‘L’estetica brechtiana e la TV’.

Available with English subtitles at <https://youtu.be/bP6aoM2dvwk?si=7oS_dH_75SMEyqpQ>.

‘Vittorio Cottafavi parle des « Cent Cavaliers »’.

Brecht, ‘A short organum for the theatre’, paragraph 55, in Brecht on Theater, ed. and trans. by John Willett (Eyre Methuen, 1978), p. 196.

Brecht, ‘Short description of a new technique of acting which produces an alienation effect’, in Brecht on Theater, ed. and trans. by John Willett (Eyre Methuen, 1978), p. 137.

‘I love Bach too much not to try to do Bach in a film. The execution scene in Fiamma che non si spegne is somewhat in the style of Bach, that is, it is constructed with horizontal and vertical sounds. The form of this scene was born out of a need to give an order to material things, so that spiritual things could be liberated’. Michel Mourlet and Paul Agde, ‘Entretien avec Vittorio Cottafavi’, Présence du cinéma, 9, December 1961, pp. 5–28. An English translation of this interview is available at <https://theluckystarfilm.net/2025/03/12/translation-corner-vittorio-cottafavi-in-presence-du-cinema/>.

Interview with Bertrand Tavernier, Positif, 100-101, p. 64. English translation published in this issue of Narrow Margin under the title 'A resigned rebel'.