Like the transformation of nature, the transformation of society is a liberating act; and it is the joys of liberation which the theatre of a scientific age has to convey. [1]

—Bertolt Brecht

Brecht’s ideas on theater, exemplified by his direction, theorized in numerous writings and above all in ‘A Short Organum for the Theatre’ (even if the author never systematically theorized them), represent today a precise achievement which, under the name of ‘the new epic’, has influenced not only the way of staging certain texts, but even the inspiration of many authors. The estrangement, this tearing of the umbilical cord linking the actor to the character and the character to the public, has liberated the character from the sentimental mud against which he floundered in bourgeois theater, linked in a single embrace to his performer and his audience, and has left him detached, free and exemplary: one ‘different from us’ with whom we can argue, who can convince us, whom we can refute; one who does not try to involve us, one who forces us to stay in our seats listening to him, and who does not allow us to go up to the stage, who does not consent to our evasion; one who leaves the actor representing him always three steps behind his back, almost as if the actor were a projection of his deflected backwards... But above all the Verfremdungseffekt — the estrangement — avoids the identification of the representation itself with the represented events. If the model for the new epic should be the ‘street scene’ as exemplified by Brecht, [2] that is, the street where an accident just happened and where the arguments, accusations and defenses of all who saw the accident solicit the ignorant wayfarer who must figure out what happened as if he were a spectator, only by the accounts of the actors — that is, of those who witnessed the crash — then a question arises: how much of theater as a whole can be transformed or reduced to the ‘street scene’ formula? Let us not forget that Brecht, when suggesting the ‘street scene’ as an example of estrangement, stated:

[...] the epic theatre is an extremely artistic affair, hardly thinkable without artists and virtuosity, imagination, humour and fellow-feeling; it cannot be practised without all these and much else too. It has got to be entertaining, it has got to be instructive. [3]

Of existing theatre, very little of what was not already born under the cold but clear light of the new epic can be staged according to its canons. Brecht himself had to radically transform texts that weren’t his own, so much so that nowadays Antigone is presented with Brecht’s name beside that of Hölderlin.

Perhaps, by excavating our immense mine of masks we may discover previous ‘epic’ texts, and that would be fair, since nothing is more estranged than the mask which is always ‘different from itself’ and which in any case refuses to yield to the spectator what it carries in its countenance, denying him any possible evasion. The most modern means of mass communication, radio and television — given the evident and almost magical technological mediation, the physical presence of the instrument and the simultaneity of the communication which singularizes the multiple and multiplies the singular in the uncontrollable rhythm of electronics, so that the spectator feels simultaneously singular and collective (an ideal situation for an ‘estranged’ spectator) — should then be the ideal instruments for the realization of epic theater. We do not know if and when the television networks of other countries have aired shows according to the epic canons, and this lack of information and documentation is a very serious obstacle not only to any research on the specific field which we are examining but also to any theoretical and historical research on the television medium.

We should therefore limit our examination only to Italian television and, for now, to the only example of which I have direct experience: Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s original radio program Operazione Vega, which was adapted [by Cottafavi himself] to the TV screen and broadcasted on July 2nd 1962.

The subject confronted by Dürrenmatt was already estrangeable in a Brechtian fashion by itself: a sci-fi-inflected fable which portrayed an anarchic society on planet Venus. The fable ends with the nuclear destruction of Venus by terrestrials.

It was necessary to prearrange the instruments of estrangement according to the means of television: the story should be narrated indirectly, that is, narrated by a narrator who would fracture each sequence, positing himself time and again as an interpreter of the narrated ‘document’ (this fracture happened 14 times in little more than one hour of program); surprise — another fundamental epic element — was entrusted in equal parts to the set design, to the lighting, to the use of the camera and to the special effects, but the set design was the most evident element of ‘surprise’ (from the spaceship with a single wall made of shiny black plastic tables which later opened like an immense window to the planet Venus, covered by the amazing whirlwinds of its atmosphere, to the long tubular corridor with the five actors reading their lines while the tube spun back and forth as if being attacked by the Venusian sea, their voices rumbling in the tube accompanied by the roar of its metal plates, and the geometrical purity of the tubular shape deforming the already twisted meanings of the men’s false words); the line-reading was based on a didactic tone, alternated with the tiredness of the characters in the rare moments when they folded in on themselves (a sort of self-pity for the character on the actor’s part, though always very brief), in such a way as to reconstruct the character from scratch after the recovery of each fracture. The fundamental tones were thus subdivided: the military commander pronounced his lines like concepts completely outside the realm of his personal interests; the undersecretary of Venusian affairs, who never appeared in person but always projected on a CCTV screen, expressed himself like a news anchorman; the three ministers, in the long political discussion, walked across the spaceship lined up one behind the other, turning together in a single movement, as if they were mechanized; the Venusians stated their reasons to the terrestrial ministers with the tenacious patience of masters trying to make themselves understood by mentally retarded creatures; and so on, up to the serene certainty of the Venusian Borst, who describes the imminent catastrophe of which he will be the instrument like a contingent and already accepted fact, incapable of altering or halting man’s evolutionary process. No musical commentary was added in order not to risk inserting a sentimental element, only electronic effects, with the same function as noises, and even the credits, projected over the illustration of a Neanderthal’s skull, were accompanied by electronic music. Every suggestion theorized by Brecht was substantially applied (including irony and wit) so that ‘the spectator [would be forced] to look at the play’s situations from such an angle that they necessarily became subject to his criticism’. [4] Now, this show — according to data from the Ufficio Opinioni [‘Bureau of Opinions’] — had a lukewarm reception by almost all spectators, and even the most favorable ones expressed many reservations. From the little information we can get from the Ufficio Opinioni however, and from the few conversations had with some spectators, it is too difficult to state a precise evaluation of the show’s merit. We can only analyze the limits of this attempt and the causes of its failure theoretically.

The three extreme cases could have been: 1) that the direction, although proceeding from very good intentions, had simply failed in its level of quality; 2) that the subject discussed by Dürrenmatt was foreign to the objective facts of our current society, and precisely because of this lacked any interest for the spectator; 3) that the TV medium was not the most suitable instrument for obtaining a consensual estrangement from the spectator.

Let us assume that, after careful and informed consideration, cases 1 and 2 turn out to be wrong; we may then dedicate ourselves to examining case 3, which immediately takes us back to our Brechtian discussion.

The TV medium, although it reaches millions of spectators simultaneously, seems to address each one of these individually, reaching them in their own houses with an intimacy of communication that establishes an original relationship of confidence and friendship. From this, it becomes clear that the relationship between spectator and TV show, although remaining within the limits of the psychological-emotional variants particular to the medium (we can’t speak of language, yet), conditions and determines the characteristics of the show.

Brecht says: ‘the smallest social unit is not the single person but two people. In life too we develop one another.’ [5] In TV, one of the men is in the video, the other in his seat, but the social unit exists because one talks to the other, who listens to him. And listens with such an intense personal relationship that he turns that face in the video into a friend, and if he recognizes him in the street is led to greet him with a frank reflex which reveals to us the hypnotic permanence particular to the TV medium.

When Brecht theorized the new epic, he had to tear down the hypnosis (‘sick dreamers’ is what he called the spectators) which led the public to a collective evasion of their social reality, an escape from morality and knowledge. He uses the word ‘immedesimazione’ when referring to the spectator’s personal relationship with the actor-character, but (assuming the Italian translation is precise) it is clear that within ‘immedesimazione’ there’s also the meaning of evasion, escape, hypnosis. [6]

Chesterton wrote that ‘there are two ways of getting home; and one of them is to stay there. The other is to walk round the whole world till we come back to the same place.’ [7]

Let’s try to think of the new epic as a highway which can be driven both ways: one is that of estrangement, the other must dialectically be that of identification. We’ve already observed that immedesimazione is evasion-escape-hypnosis; now, identification [identificazione] is consent-participation-taking a stance. Through identification, the spectator’s commitment isn’t limited to that restricted field of human relations inside which the actions of the drama develop, but expands through a reverberation in his own time and his own space, now real and no longer virtual, since the spectator has shattered the limits of the spectacle by identifying himself and referring it to his own direct experience according to the dialectical terms of his way of living.

If evasion is closing oneself, a refusal, then identification is remaining open, it is consent.

Isn’t it perhaps precisely through identification that we can recover remorse? Or rekindle joy? Or affirm a commitment?

Brecht also says: ‘The object of the performance is to make it easier to give an opinion [giudizio] on the incident.’ [8]

And couldn’t this identification-participation perhaps be the very substance of consent (or of refusal), the ultimate consequence of a judgement [giudizio]? Isn’t this perhaps the way to achieve clarity?

These are questions which will continue to await an answer, since what is being proposed here is a line of research and experimentation which, by using estrangement as indirect experience, has led to us finding the formula congenial to the new instrument of mass communication, TV. If we manage to see this mass of spectators in the intimacy of each one of them, in the secrecy of communication, in the smallest social unit, man plus man united through the TV screen, then we can very well conceive that through the consent and the identification of each one of them we can create a collective tide built out of each individual taking of a stance, each individual affirmation of conscience, each individual conquest of thought, which can and must determine man in his involvement and in his mutual development between one and all.

If the TV-instrument is born under the sign of man, if its strength is in being equal to the measure of man, in being inserted into his everyday life, then we must believe that it is possible, that it is necessary to find that which henceforth we will call the camera epic.

From Ai poeti non si spara: Vittorio Cottafavi tra cinema e televisione (Edizione Cineteca

di Bologna, 2010), pp. 142–144. Originally published in Televisione, 1, April 1964.

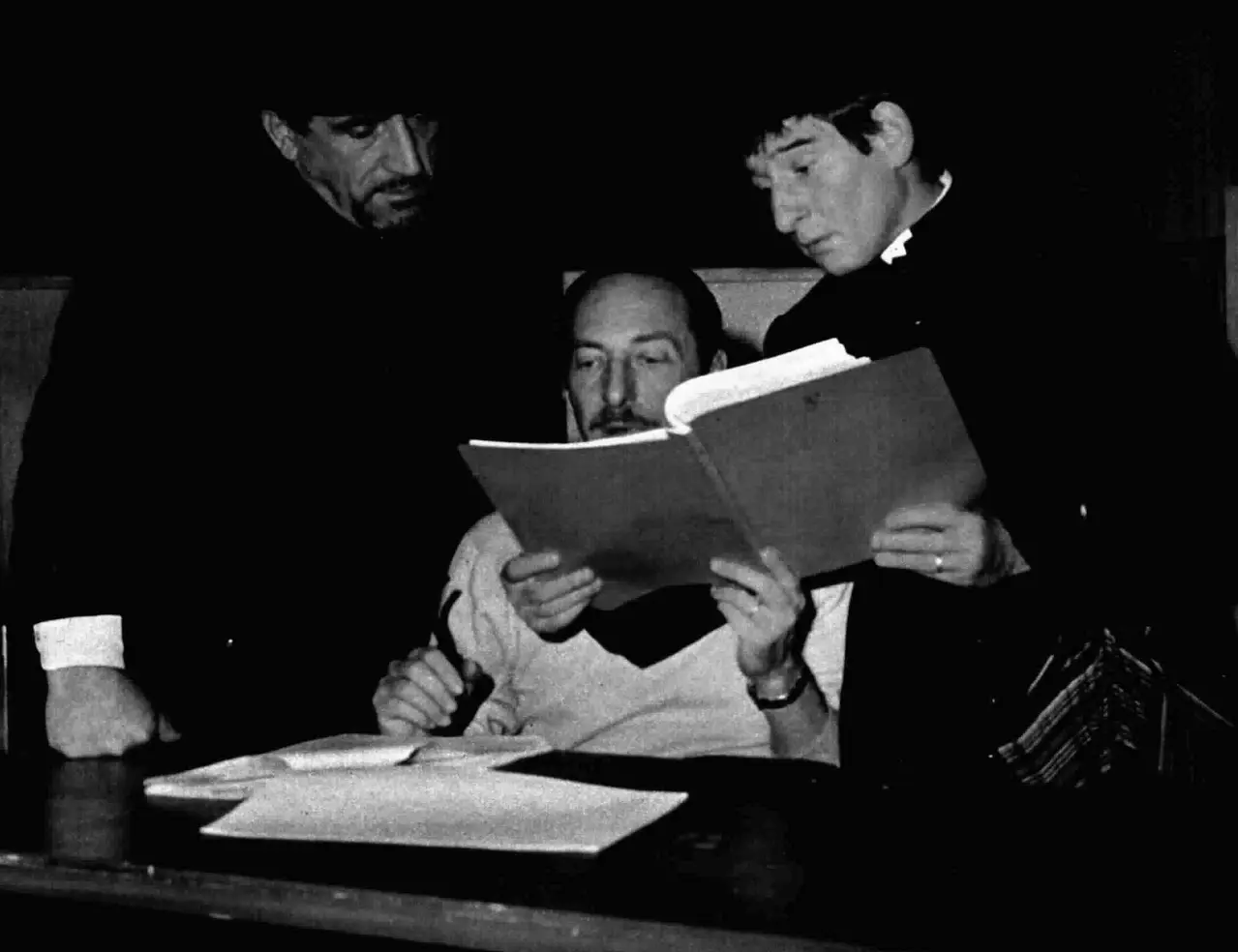

Vittorio Cottafavi with Arnoldo Foà and Renato Rascel on the set of I racconti di Padre Brown (1970).

Notes

Bertolt Brecht, ‘A Short Organum for the Theatre’, aphorism 56, in Brecht on Theater, ed. and trans. by John Willett (Eyre Methuen, 1978), 179–205 (p. 196).

See ‘The Street Scene: A Basic Model for an Epic Theatre’, in ibid., pp. 121–29.

Ibid., pp. 126–27.

Ibid., p. 20.

‘A Short Organum for the Theatre’, aphorism 58, p. 196.

Translator’s note: The Italian word immedesimazione is usually translated as ‘identification’ and even in Italian is sometimes considered as synonymous with identificazione, but Cottafavi makes a distinction between the two. Immedesimazione is constructed from the word medesimo, which means ‘same’; something like ‘same-fication’, the process of equating two things; while for him, identification (identificazione) seems to be more dialectical (probably nothing of this has anything to do with Brecht’s writings in German, where the word Identifikation is used).

G. K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man (Dodd, Mead & Company, 1925), p. xi.

‘Street Scene’, p. 127.