Love, unconquered in the fight. Love, who makest havoc of wealth, who keepest thy vigil on the soft cheek of a maiden. Thou roamest over the sea, and among the homes of dwellers in the wilds. No one can escape thee, no immortal, nor any among men whose life is for a day. And he to whom thou hast come is mad [1]

—Sophocles, Antigone, ll. 781–790

The death of Antigone is well known. Vittorio Cottafavi’s 1958 television film is a faithful production of a staging of Sophocles’ play, translated into Italian by Enzo Cetrangolo. Oedipus’s brother Creon (Antonio Crast) has secured the throne of Thebes after a battle between Oedipus’s sons Polynices and Eteocles has resulted in both of their deaths. Polynices has aggrieved Creon in his betrayal of Thebes and the king has prohibited him a proper burial. Antigone (Valentina Fortunato) and Ismene (Elena Cotta), the remaining children of Oedipus, are distraught and meet to discuss burying Polynices in violation of Creon’s decree — this is where the Antigone begins.

When Creon discovers Antigone has gone on with her plan, she is entombed alive. Antigone commits suicide inside the cave that has sealed her away from the living, as does her bretrothed, Haemon, Creon’s son. When news of this reaches Eurydice, Creon’s wife, she kills herself too, leaving the new King of Thebes alone at the end of the film. Antigone dies for her devotion to her brother. Her allegiance is to love, not her society. In the context of Italian cinema of the time, Cottafavi’s film recalls Ingrid Bergman in Europa ’51 (1952), who is deemed insane by the bureaucratic order of post-war Italy for her devotion to love. The war had changed the way Europe viewed Sophocles’ Antigone — the Nazis claimed it as their heritage, [2] with Antigone performed over 150 times in Germany between 1939 and 1944. [3] Heidegger's lectures on Hölderlin’s Antigone, though they caution against the reading of Antigone as a National Socialist, [4] nevertheless added to this myth. On the other hand, Antigone herself became a symbol of antifascist resistance for those in Nazi-occupied Paris who saw Jean Anouilh’s adaptation in 1944. When Brecht’s version premiered in Switzerland four years later, he did not see Antigone as a heroine (she was a member of the ruling family of Thebes, which she did not set out to destroy, but to honor), but simply as a duty-bound sister. In the words of the classicist Martin Revermann, ‘Brecht lets his Antigone “do what Antigones do”’. [5] Still, his Antigone opens with a prelude of explicit, anachronistic opposition to the Nazis. It is in the context of imagining what Antigone might look like in a post-war Europe that Cottafavi directed two adaptations for RAI (Radiotelevisione Italia) in 1958 and 1971. How did he see Antigone in 1958? Like Brecht, he understands Antigone herself not primarily as a political figure. Unlike in the Brecht version, there is no prologue in 1958; all Cottafavi will present is an act, not of civic or religious duty, but of love.

I

Antigone is like a sunbeam, a beam emitted from the ground which lays at her feet. [6]

—Cottafavi, ‘Notes for the mise en scène of Sophocle’s Antigone’, 1962

There is a spiritual expression from the book of Genesis that describes a miraculous passageway to heaven as seen in a vision of Jacob — ‘Jacob’s ladder’ — which can be used colloquially to describe a certain type of a sunbeam that appears through clouds. Cottafavi’s mise en scène is arranged to lead the audience’s gaze upward, where Antigone is often positioned. She is surrounded by a dark volume, the society of Thebes, but remains a vessel of light — if the image of Jacob’s ladder summons a sunbeam proceeding not from the heaven to the earth, but from the earth to the heavens, Cottafavi’s Antigone literalizes this image of ‘a beam emitted from the ground’. He proposes an impossible order of physics to illuminate the ways in which Antigone defies all that is around her, and this defiance is carried through into how he films her: always vertical, upright. She does not succumb to the burden of death — she does not fall, as almost everyone around her does. The entire film is constructed so that the geometry of a given scene expresses moral relations. To achieve this, Cottafavi constructed an austere set, so that his camera could more easily navigate the ever-shifting positions of the film’s characters in real time.

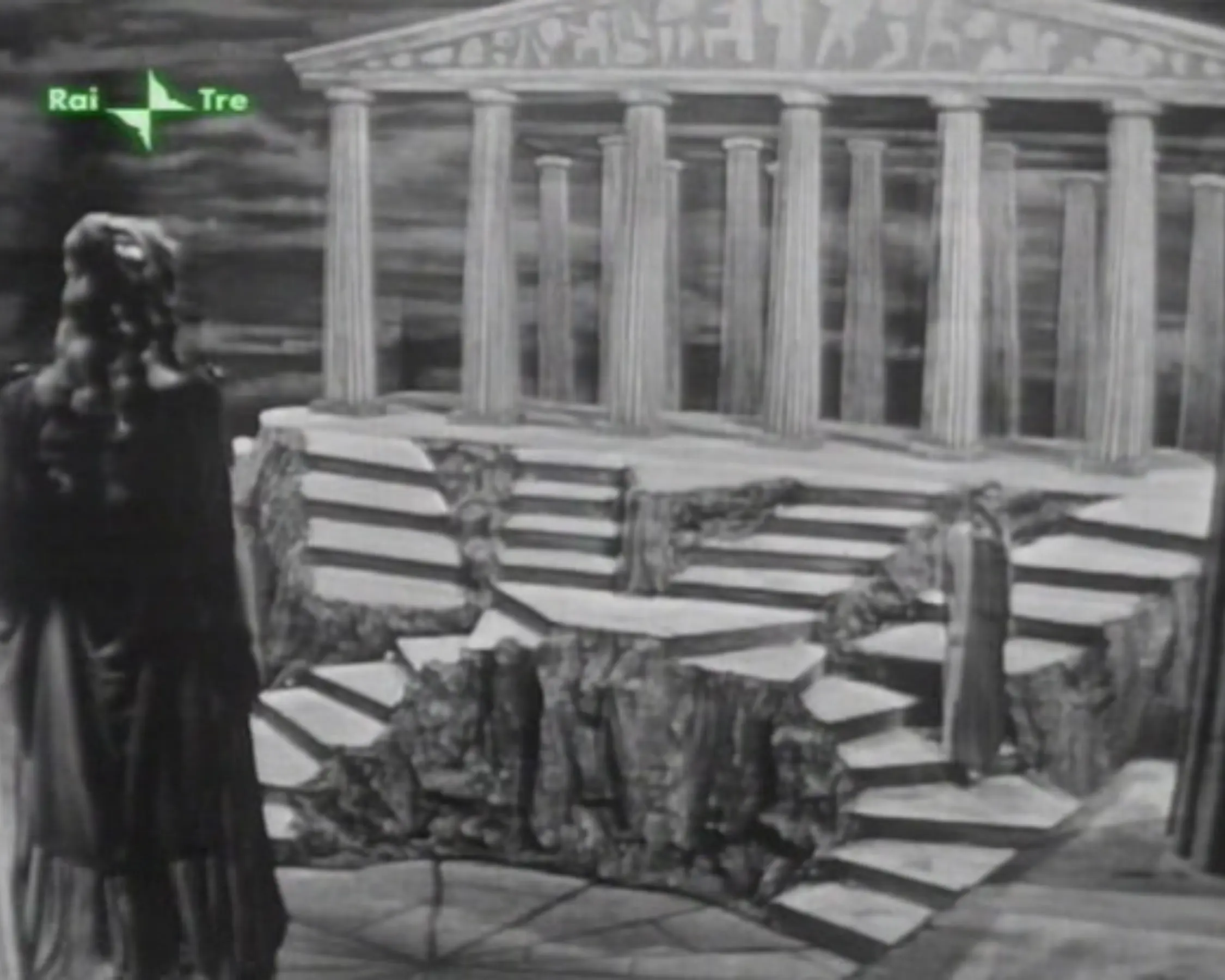

Thebes is built between two opposite colonnades: the temple and the palace, overlooking an agora in the center. Every action is confined to the single location, as would have been the case in ancient theater. The first movement in the film is Antigone’s. She enters from the right, descending the staircase of the temple. A shot from behind Ismene at the top of the palace steps shows her sister at first much lower, but Ismene’s descent results in Antigone looking down on her. They meet in the circle between the carved stone slopes surrounded by the pillars of their society. It is not a coincidence that Antigone and Ismene arrive from the places they do. Ismene, the poor and faithful mourning sister, is bound to her life as a citizen of Thebes: ‘But to defy the State, I have no strength for that’ (ll. 78–9). Antigone doesn’t believe. She doesn’t believe in the sanctity of law, which would dictate her subservience to Creon’s decree; she doesn’t believe in the gods to resolve the matter of Polynices’ burial, which does present a spiritual crisis for Thebes — the gods did intervene. The classicist Gilbert Norwood writes in Greek Tragedy (1920) that ‘there is a logic of the heart that has little to do with the logic of the brain. Antigone has no reasons ; she has only an instinct.’ [7] It is not fate or destiny or a god that guides her actions. ‘Fate isn't a fact external to man, imposed upon man,’ writes Cottafavi in relation to Antigone, ‘it grows within man himself, out of man himself, and determines events through man's voluntary actions: thus man participates in divinity. Antigone is a mirror: the mirror of her own myth.’ [8] There is a fundamental strangeness to her; or, following Heidegger’s translation of the Greek δεινόν, she is suffering the uncanniness or unhomeliness (unheimlich, in German) that appears to her, which reveals itself as a death wish. [9] It is Antigone’s movement downwards, towards death, that traces her transcendence of this society. So her first movement in the film is to go down — but even then, she remains elevated above the citizens of Thebes, represented here by Ismene.

The dialogue between the two sisters follows the opening credits, which feature a score that fuses electronic elements with a choral overture. There is a dissonance between the avant-garde electronic score and harmonized communal singing, a practice that can be traced to ancient Greece, priming the audience’s ear for what was another novel audio technique: Fortunato and Cotta’s voices are captured using direct sound, a tool rarely employed by Italian filmmakers of this time. As we have already seen, Cottafavi’s film uses the vacuums between characters as realizations of the moral distance or as measures of the separations of power between them, the superior above the inferior. Cottafavi’s use of direct sound causes every gesture to have an added sonic weight, every turn away from the camera presents a diminution in the clarity of a voice. Distance is therefore realized in both the eye and the ear. This is an early manifestation of Cottafavi’s Brechtian impulses applied to the medium of film, which were not wholly liberated until Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide (1961). As the sisters’ argument over whether or not to bury the dead crescendoes in intensity, Antigone rises to the top of the temple steps, but hers are not the only footsteps perceived. There is creaking, some isolated grunts, and even the passing shadow of a microphone as crew members on set work to keep up with the action. The film was broadcast live. While these artifacts of labor do not go as far as Cottafavi’s Brechtian fourth-wall breaking in the 1971 Antigone, which includes an intermission that reveals the film set, it is a reminder of the fact that the time and space of Antigone are not manufactured. The stage is as sparse as it is to allow the maximum amount of flexibility of movement for both the actors and the crew in this live setting. In the end, Antigone stands straight, tall, while Ismene bends towards her, buried in her bosom. According to Cottafavi’s conception of the characters, ‘Antigone is a straight line … Ismene is a triangle’. [10] And here, at the dissolution of the sisterly relationship, they resemble their prescribed geometries, Antigone standing tall above a vertically compromised Ismene.

II

There are situations in which I feel the need to orient the totality of events according to a certain construction in the image […] in particular […] Antigone. [11]

—Cottafavi, Entretien avec Vittorio Cottafavi, 1961.

Cottafavi discusses many geometries in his notes for the mise en scène for Antigone, relating both to the characters and to the camera (‘All scenic action shall develop in vertical lines, going up and down’). [12] It is not Sophocles’ stage directions that guide these decisions — for none survive — but Cottafavi’s own mathematical drive. Consider the geometry of the camera work during the first choral ode. It is the scene after Antigone has declared to Ismene her intent to bury Polynices. The chorus is arranged in a horizontal line along the pillars of the palace, the camera positioned alongside them, looking down the line at a slight angle. One member begins to walk down the stairs, opening the ode: ‘Beam of the sun, fairest light that ever dawned on Thebes of the seven gates’ (ll. 100–1). It is at this point, before he has even finished his sentence, that the camera cuts to a new angle — lower, shot from a large stone platform halfway down the stairs. The ode continues, providing background to Antigone’s actions and the current state of Thebes. The chorus details the fratricidal battle, and describes the new ruler who has risen from this struggle, Creon. Most of the ode is presented in the second camera position, the most dynamic, moving across the agora to frame and reframe all four members of the chorus as they speak their part — the next member of the chorus to speak is always positioned in the background, above the last, and each descends the stairs in turn, moving across and down the frame in accordance with the patterning of the architecture until they are halfway down the flight. A third camera position interrupts this rhythm, as the first chorus member takes center stage and makes his way into the agora. The next four camera positions only focus on one chorus member’s part of the ode, and the following chorus member’s coordinates are established in the background of the present one, as each in turn makes his way into the center of the set. Many of the visual propositions Cottafavi makes about the characters’ verticality could be accomplished in theatre; this is blocking. But the way that Cottafavi manipulates their positions with the angle of his camera heightens the geometry — if this were only a stage play, the audience would see the chorus walk down the stairs in unusual arrangements, but it is only when given access to these six unique angles that one is presented the rhymes of the bodies descending.

In the context of the rest of the ode, the ‘beam of the sun’ the chorus mentions would appear to refer to the new day that has dawned upon Thebes. They exalt Creon as the city’s ruler and Eteocles as its protector from Polynices’ wrath. However, taken alone, and presented as it is just after Antigone’s ascent of the vertical axis, this line would appear to position her as the ‘fairest light that ever dawned’ on Thebes. It is no coincidence that in his notes for the mise en scène Cottafavi describes Antigone as a sunbeam — he has chosen a metaphor that reflects the first choral ode in the play. The reading of Antigone as a sunbeam is reliant on Forunato taking on the role of the light she is born into, as she ‘is’ only the traces of light that resemble her as captured by the camera’s eye. This effect is manipulated by Cottafavi’s allotment of light to her, particularly in her death march, which will be discussed in the next part of this essay. The last chorus member announces Creon, ‘our new ruler by the new fortunes given by the gods’ (ll. 156–8). This is the point at which Creon enters for the first time. Here, the camera position, the seventh in the scene, is a reflection of the first — looking down a horizontal line across the pillars of the palace. He walks along the line of his army, their spears pointed up, and exalts himself, before descending to address the chorus. A moment of brilliance from Cottafavi: Creon is positioned above his council, now a mass of men where previously there were only four. He walks down the final set of stairs, and joins them on the lowest plane, speaking:

ᴄʀᴇᴏɴ No man can be fully known, in soul and spirit and mind, until he hath been seen versed in rule and law-giving.

(ll.175–7)

It is here, when he is finally at the lowest position, that he reaffirms his order that Polynices should not be buried, before hearing the news that he has been defied. During Antigone’s trial, which follows the second ode and the discovery of her act, he attempts to reason with her regarding Polynices’ betrayal of Thebes.

ᴄʀᴇᴏɴ A foe is never a friend, not even in death.

ᴀɴᴛɪɢᴏɴᴇ Tis not my nature to join in hating, but in loving.

(ll. 522–3)

It is at this point Creon stumbles in his accusation: he cannot refute or contend with this. He is no longer reasoning with Antigone, but is humiliated by her devotion. He turns his back to her as he condemns her to the grave, and walks down the stairs to the lowest level of the scenery before finishing his insult.

ᴄʀᴇᴏɴ Pass, then, to the world of the dead and if thou must needs love, love them! While I live, no woman shall rule me!

(ll. 524–5)

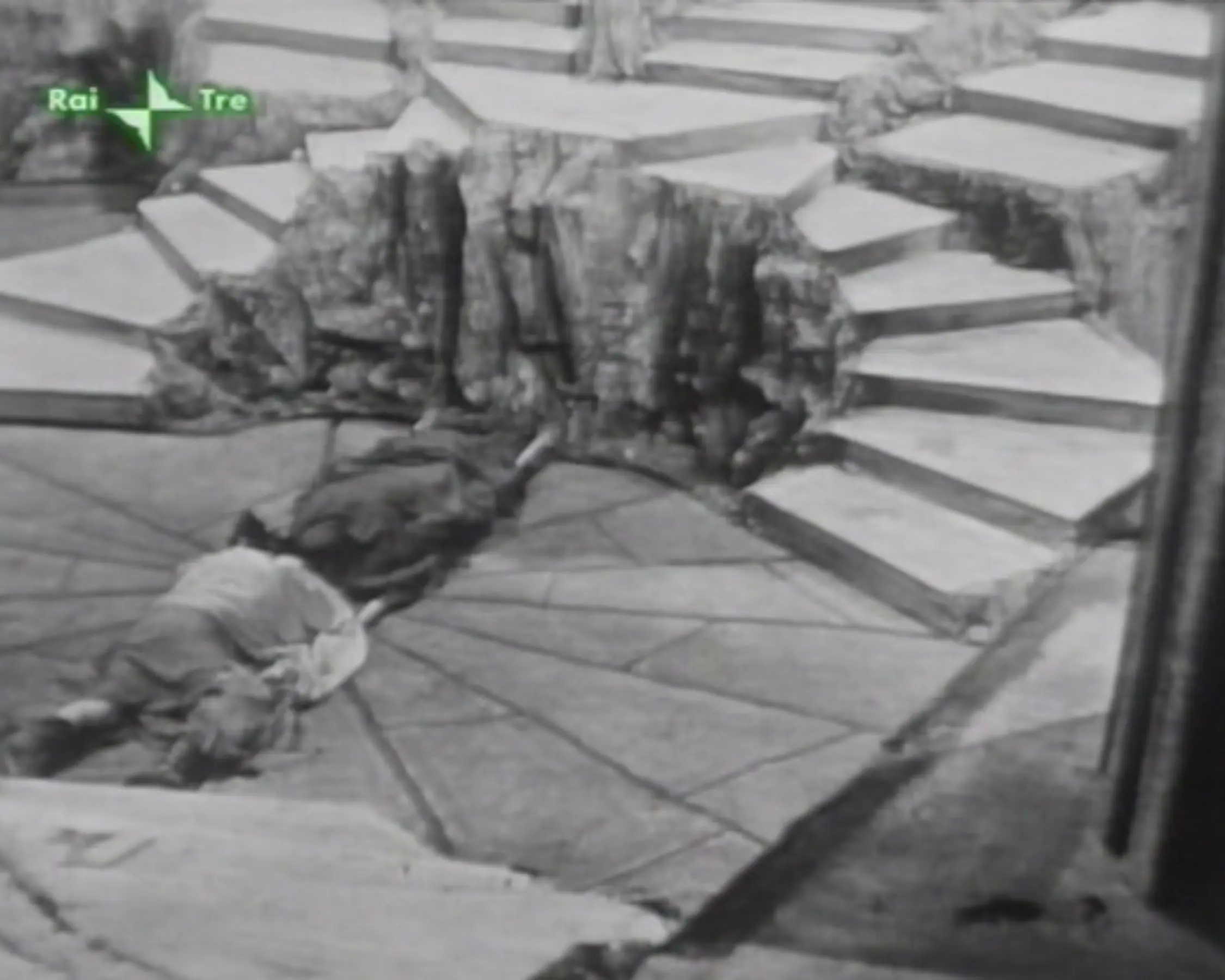

Ismene enters the trial, and Creon looks up at her. The sister has come to join in Antigone’s fate. Ismene is elevated above Creon and the audience, not unlike Antigone. She looks up, signaling an ever higher calling when she tells Creon that ‘I have done the deed...’ in reference to the burial of her brother. She must, however, lower her gaze to meet Antigone’s eye to finish her plea, ‘...if she allows my claim...’ Now, Ismene walks down the stairs, and her vision becomes more intense as she humbles herself geometrically before Antigone, continuing, ‘...and share the burden of the charge.’ Antigone looks down on her sister, denying her. Ismene begs, and with every line reading descends further down the steps, until she is at the base of the rock that outcrops from the stairs Antigone is positioned on — clinging to it for support, the weight of these matters bearing on her so heavily she cannot stand upright. The trial ends, and Antigone moves ever closer to death.

![‘During the trial, Antigone will be placed up high, almost on top of a pedestal in front of the temple. Creon exits the palace and walks down the staircase, accusing her, then he goes on in the agora, low, crushed by her, tall, vertical.’ [13]](https://narrowmargin-backend.onrender.com/media/images/articles/SUMMER%202025/antigone-is-a-sunbeam/6.webp)

‘During the trial, Antigone will be placed up high, almost on top of a pedestal in front of the temple. Creon exits the palace and walks down the staircase, accusing her, then he goes on in the agora, low, crushed by her, tall, vertical.’ [13]

III

[…] The just themselves have their minds warped by thee [Love] to wrong, for their ruin, ‘tis thou that hast stirred up this present strife of kinsmen. Victorious is the love-kindling light from the eyes of the fair bride. It is a power enthroned in sway beside the eternal laws. For there the goddess Aphrodite is working her unconquerable will. But now, I also am carried beyond the bounds of loyalty, and can no more keep back the streaming tears, when I see Antigone thus passing to the bridal chamber where all are laid to rest. [14]

—Sophocles, Antigone, ll. 791–805.

This is the ode sung to Antigone by the chorus when it is time for her final actions. Antigone looks to the sky and laments the fact that she is looking at her last sunlight. As she walks she is separated from the beam of light upon her by overhead architecture, casting her into shadow. As she realizes that she is shrouded in darkness, she turns her gaze downwards, and only then does the light re-appear, as if it was always inside her, and did not depend on external conferment. The light operates this way, casting her into shadow at the slants between words: ‘Setting forth, on my last way, looking my last on the sunlight that is for me no more’ (ll. 808–10). Antigone’s final procession is one of intense vertical propositions. She enters from the left, walking along the palace’s high exterior, before making her way down the stairs of the palace, whose foundation now seems larger than in previous scenes. The chorus engages with her pleas, encouraging her advance towards Hades. Antigone contemplates her parentage, and the curse of incest of which she is the product. Between her next two lines, her face becomes shrouded in shadow. ‘From what manner of parents did I take my miserable being! / And to them I go thus, accursed…’ (ll. 866–7). She is only fully liberated from this darkness, that is, her face only appears fully veiled in light again, at the line, ‘No longer, hapless one, may I behold yon day-star’s sacred eye!’ (ll. 877–880). This is a re-affirmation of the light of Antigone, that though she may come from Oedipus’s error and inhabit the shadow this has cast on Thebes, she transcends the dark volume of the city. Antigone will not see the light again, but she is still embodied as light. She climbs back up the steps of the temple, passing along its columns, and casts a final look downwards, towards Creon, before a final descent. ‘Antigone does not go toward death, she descends into it, she submerges herself as if in water. The last image of her shall descend and disappear from the bottom of the frame.’ [15]

IV

We tread with uncertainty, for we are caught between an infinity and an abyss of quantity, an infinity and an abyss of movements, an infinity and an abyss of time from which we can learn to truly know ourselves and enrich ourselves with thoughts worth more than the whole of geometry. [16]

—Pascal, Of the Geometrical Spirit, 1658

After Antigone is sentenced to death and before her final moments, Haemon advocates for her to be spared execution. Crast portrays Creon as an immovable object. Though he would like to appear reasonable, his tone betrays him and his attitude reflects contempt for his society. In the final moments of a political battle precipitated by Antigone’s death, Haemon stands over him — Creon is positioned low once again, now at the feet of his own son.

The only man who can move Creon is Tiresias (Ennio Balbo), the blind prophet. After Antigone’s tomb has been sealed, Tiresias comes to Creon to warn of the perils that lie in store if the matter of the burial of Polynices and Antigone is not settled. The gods have rejected his sacrifice, and impending danger awaits Thebes. Cottafavi frames the large part of Tiresias's omen in four camera movements. Each opens with a medium shot capturing both Creon and Tiresias, before the camera rushes in to a close-up of Tiresias, lastly capturing Creon’s reaction before widening out again; the first movement approaches the pair from the right, the second from the he left, and then the dynamic repeats for the third and fourth shots. An attentive audience member will notice that Tiresias’s head is always elevated, he is ‘looking’ ahead, above, and his bald head shines bright under the harsh studio lighting. Creon, in his close-ups, is perpetually facing down, his gaze shrouded in darkness.

After the omen is pronounced, Creon rebukes Tiresias, and so squanders his only chance to correct the record. Tiresias’s eyes light up as he looks directly into the heavens. Angrily, the prophet announces (no longer warning) that the house of Creon will suffer, ‘a corpse for a corpse’. Again Creon’s face is engulfed in darkness as he looks down. The King of Thebes, to avert disaster, buries Polynices and attempts to fetch Antigone from her grave — he’s too late. Antigone’s suicide is switfly followed by Haemon’s own, and is related to Eurydice, who kills herself as well.

Cottafavi describes Creon as ‘a hexagon that in the epilogue is shattered and disperses into triangles. Let us remember his final scream: “All that is mine wobbles, oblique. All my life falls under the crushing fate which struck me in the forehead.”’ [17] Why a hexagon? We can find this shape, too, in Creon’s physicality. Time and again, he strikes a pose of power, elbows out and fists against his torso to make himself appear larger.

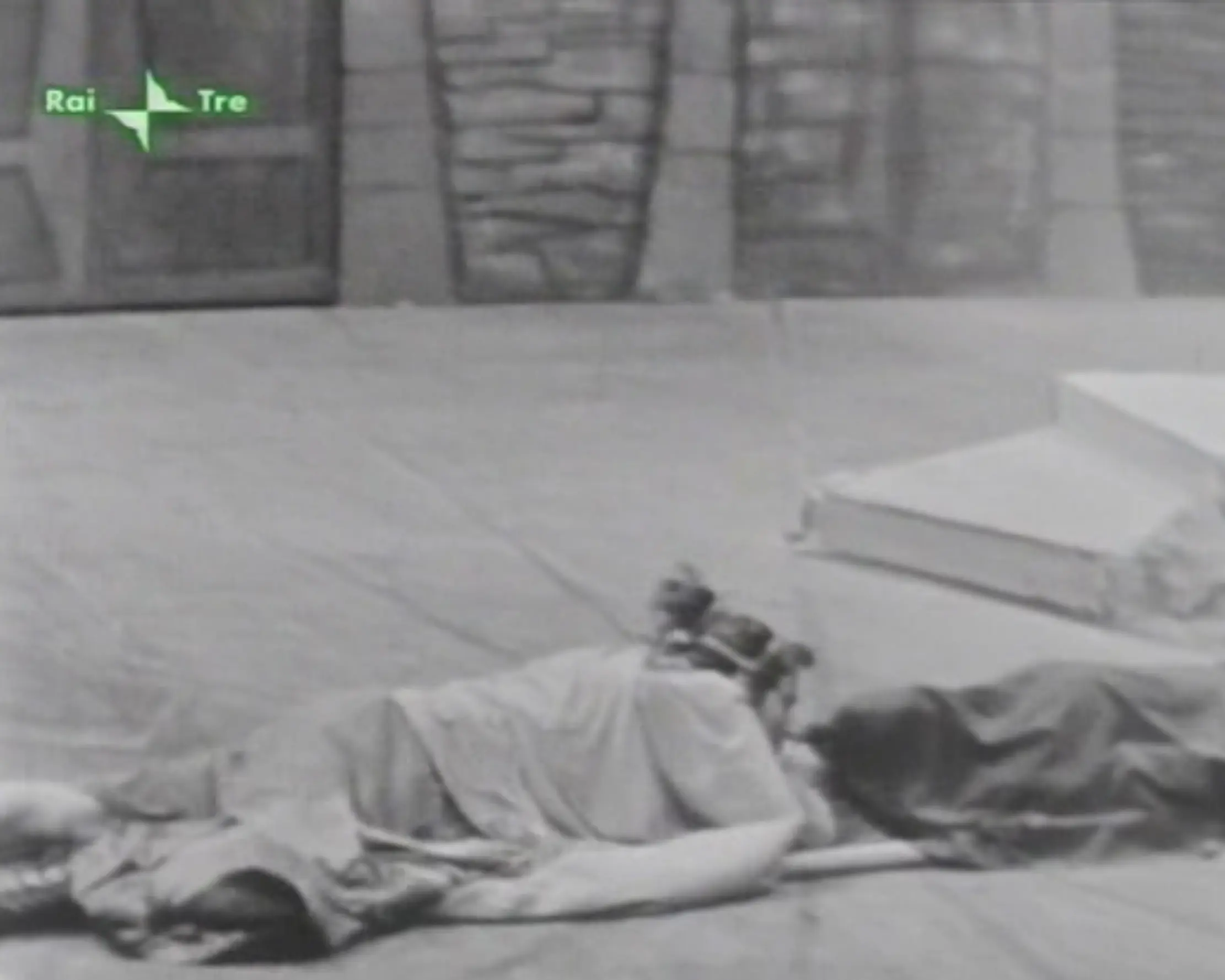

Consider Creon as a hexagon, and the six triangles he will break into. Count the deaths hanging over Creon at the end of the film: Polynices, Eteocles, Antigone, Haemon, and Eurydice. No wonder he is shattered this way, left alone, base, fallen, a fractured whole of the unified kingdom he sought to protect. ‘Oh, let it come, let it appear, it will be beautiful, that fairest of fates for me, that brings my last day, come, aye, best, fate of all! Oh, let it come, that I may never look upon to-morrow’s light’ (ll. 1328–32). The last sequence of images depicts his fall. But even here he is not granted the fate he wishes, to collapse out of the bottom of the frame. Instead, he is made abject, laid flat on the ground, at the lowest point reached by any living character. At this point, Cottafavi’s camera rises to the temple steps from which Antigone first emerged — Creon will have to face the light.

Notes

All citations from Sophocles, Antigone, in The Tragedies of Sophocles Translated into English Prose, trans. by Richard Jebb (Cambridge University Press, 1917), p. 153.

See Rossana Zetti, ‘Antigone’s (mis)appropriations in Twentieth-Century Europe: Memory, Politics and Resistance’, in Calíope Presença Clássica, 34:2 (February 2017.), pp. 4–21.

Ibid., p. 8.

Martin Heidegger, Holderlin’s Hymn “The Ister”, translated by. William McNeill and Julia Davis (Indiana University Press, 1996), p. 80.

Martin Revermann, Brecht and Tragedy: Radicalism, Tradition, Eristics (Cambridge University Press, 2022), p. 133.

Cottafavi, ‘Notes for the mise en scène of Sophocles’ Antigone’, trans. by Gabriel F. de Carvalho in this issue of Narrow Margin. Originally published in French as ‘Notes pour la mise en scène d’Antigone de Sophocle’ in Présence du Cinéma, 9, December 1962, and later in Italian as ‘Antigone’ in Televisione, 1, April 1964. https://narrowmarginquarterly.com/01/notes-for-the-mise-en-scene

Gilbert Norwood, Greek Tragedy (Methuen & Co., 1920), p. 139.

Cottafavi, ‘Notes’, p. 40.

Heidegger, p. 52.

Cottafavi, ‘Notes’, p. 40.

Michel Mourlet and Paul Agde, ‘Entretien avec Vittorio Cottafavi’, Présence du cinéma, 9, December 1961, pp. 5–28 (p. 10). An English translation of this interview is available at https://theluckystarfilm.net/2025/03/12/translation-corner-vittorio-cottafavi-in-presence-du-cinema/.

Cottafavi, ‘Notes’, p. 33.

Cottafavi, ‘Notes’, p. 34.

Sophocles., p. 154.

Cottafavi, ‘Notes’, pp. 34–35.

Blaise Pascal, Of the Geometrical Spirit, translated by O.W. Wight (P.F. Collier and Son, 1910) p. 444.

Cottafavi, ‘Notes’, p. 40, quoting ll. 1344–6.